Peripheral artery disease of the upper and lower extremities is discussed below.. Other vascular diseases, including abdominal aortic aneurysm, thoracic aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection, renal artery stenosis and occlusion, fibromuscular dysplasia, mesenteric ischemia, and ischemic stroke resulting from carotid artery stenosis are presented elsewhere.

Etiology of Peripheral Artery Disease

The global prevalence of peripheral artery disease (PAD) is between 2 and 6% overall; prevalence increases to 15 to 20% after age 80 (1, 2, 3).

Risk factors are the same as those for atherosclerosis (4, 5):

Cigarette smoking (including passive smoking) or other forms of tobacco use

Dyslipidemia (high low-density lipoprotein [LDL] cholesterol, low high-density lipoprotein [HDL] cholesterol)

Family history of atherosclerosis

High homocysteine level

Increasing age

Male sex

Obesity

Atherosclerosis is a systemic disorder; the majority of patients with PAD also have clinically significant coronary artery disease (CAD) or cerebrovascular disease (6).

Etiology references

1. Aday AW, Matsushita K. Epidemiology of Peripheral Artery Disease and Polyvascular Disease. Circ Res 2021;128(12):1818-1832. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.318535

2. GBD 2019 Peripheral Artery Disease Collaborators. Global burden of peripheral artery disease and its risk factors, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Glob Health 2023;11(10):e1553-e1565. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00355-8

3. Polonsky TS, McDermott MM. Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease Without Chronic Limb-Threatening Ischemia: A Review. JAMA 2021;325(21):2188-2198. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.2126

4. Gornik HL, Aronow HD, Goodney PP, et al. 2024 ACC/AHA/AACVPR/APMA/ABC/SCAI/SVM/SVN/SVS/SIR/VESS Guideline for the Management of Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Circulation 2025 Apr 8;151(14):e918. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001329]. Circulation 2024;149(24):e1313-e1410. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001251

5. Mazzolai L, Teixido-Tura G, Lanzi S, et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of peripheral arterial and aortic diseases. Eur Heart J 2024;45(36):3538-3700. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehae179

6. Kullo IJ, Rooke TW. CLINICAL PRACTICE. Peripheral Artery Disease. N Engl J Med 2016;374(9):861-871. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1507631

Symptoms and Signs of Peripheral Artery Disease

Peripheral artery disease may be categorized into 4 subsets: asymptomatic, chronic symptomatic, chronic limb-threatening ischemia (CLTI), and acute limb ischemia (ALI) (1). Symptoms of occlusive peripheral artery disease may not occur until the luminal diameter is narrowed by 50 to 70%, depending on the specific artery and patient. More than 20% of patients with peripheral artery disease have no symptoms, and nearly the same percentage of patients have atypical symptoms (eg, nonspecific exercise intolerance, hip or other joint pain) (1).

Patients with asymptomatic PAD may have functional impairment, as well as symptoms unmasked during objective walking tests (despite experiencing no exertional symptoms in daily life) (1).

Intermittent claudication is the typical manifestation of chronic symptomatic PAD. Intermittent claudication is a painful, aching, cramping, uncomfortable, or tired feeling in the legs that occurs during walking and is relieved by rest (1). Claudication usually occurs in the calves but can occur in the feet, thighs, hips, buttocks, or, rarely, arms. Claudication is a manifestation of reversible, exercise-induced ischemia, and it is typically relieved by rest. With mild claudication, patients are able to perform exertional activities with few limitations. As PAD progresses, the distance that can be walked without symptoms may decrease.

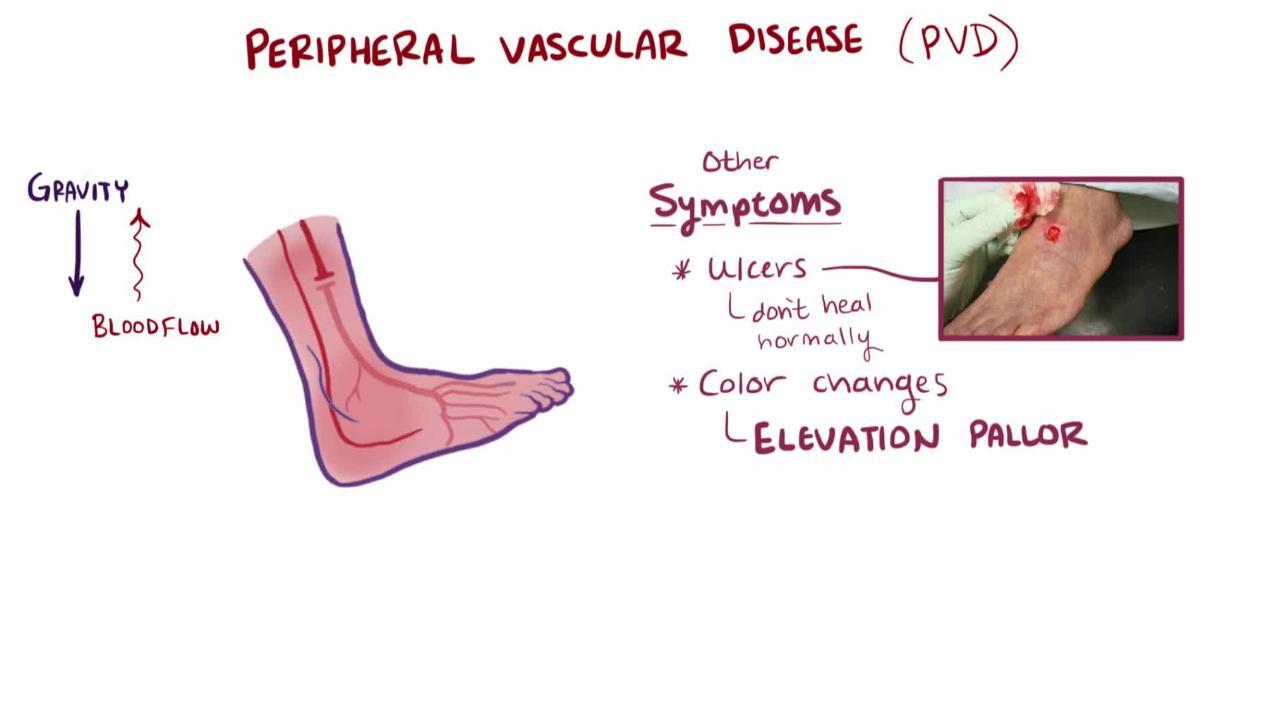

Patients with chronic limb-threatening ischemia may experience ischemic rest pain, which is usually worse distally, is aggravated by leg elevation (often causing pain at night), and lessens when the leg is below heart level (1). The pain may be described as burning, tightness, or aching, although this finding is nonspecific. When below heart level, the foot may appear dusky red or darker than usual (called dependent rubor). In some patients, elevating the foot causes loss of color and worsens ischemic pain; when the foot is lowered, venous filling is prolonged (> 15 seconds). Edema is usually not present unless the patient has kept the leg immobile and in a dependent position to relieve pain. Patients with chronic PAD may have thin, pale (atrophic) skin with hair thinning or loss. Distal legs and feet may feel cool. The affected leg may sweat excessively and become cyanotic, probably because of sympathetic nerve overactivity.

Sudden, complete occlusion is discussed in Acute Limb Ischemia.

DR P. MARAZZI/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

As ischemia worsens, ischemic ulcers may appear (typically on the toes or heel, occasionally on the leg or foot), especially after local trauma. The ulcers tend to be surrounded by black, necrotic tissue (dry gangrene). They are usually painful, but patients with peripheral neuropathy (eg, due to diabetes or alcohol use disorder) may not feel them. Infection of ischemic ulcers (wet gangrene) occurs frequently, typically leading to rapidly progressive cellulitis.

The level of arterial occlusion influences location of symptoms. Aortoiliac PAD may cause buttock, thigh, or calf claudication; hip pain; and, in men, erectile dysfunction (Leriche syndrome). In femoropopliteal PAD, claudication typically occurs in the calf; pulses below the femoral artery are weak or absent. In PAD of more distal arteries, femoropopliteal pulses may be present, but foot pulses are absent. Patients with chronic limb-threatening ischemia typically have multisegment disease (eg, aortoiliac, femoropopliteal, and tibial occlusions).

Peripheral artery disease occasionally affects the arms, especially the left proximal subclavian artery, causing arm fatigue with exercise and occasionally embolization to the hands.

Symptoms and signs reference

1. Gornik HL, Aronow HD, Goodney PP, et al. 2024 ACC/AHA/AACVPR/APMA/ABC/SCAI/SVM/SVN/SVS/SIR/VESS Guideline for the Management of Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Circulation 2025 Apr 8;151(14):e918. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001329]. Circulation 2024;149(24):e1313-e1410. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001251

Diagnosis of Peripheral Artery Disease

Ankle-brachial index

Ultrasound

Angiography (includes magnetic resonance angiography, CT angiography, or invasive angiography)

© 2017 Elliot K. Fishman, MD.

Peripheral artery disease is underrecognized because many patients have atypical symptoms or are not active enough to have symptoms. Spinal stenosis may also cause leg pain during walking but can be distinguished because the pain (called pseudoclaudication) requires sitting, not just rest, for relief, and distal pulses remain intact.

Diagnosis is confirmed by noninvasive testing. First, bilateral arm and ankle systolic blood pressure (BP) is measured using Doppler probes and a manual blood pressure cuff. Segmental blood pressure measurements are often used, because pressure gradients and pulse volume waveforms can help distinguish isolated aortoiliac PAD from femoropopliteal PAD and below-the-knee PAD.

JIM VARNEY/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

The ankle-brachial index (ABI) is the ratio of the highest ankle systolic BP (on the right and left) divided by the highest arm systolic BP. A low (≤ 0.90) ankle-brachial index is diagnostic of lower extremity PAD, a value from 0.91 to 0.99 is borderline (1).

If the index is normal (1.00 to 1.40) or borderline (0.91 to 0.99) but suspicion of PAD remains high, an exercise ABI can be measured using treadmill walking or ankle lifts. After exercise, a drop in the ABI by 20% is diagnostic of lower extremity PAD. A high resting ABI index (> 1.40) may indicate noncompressible leg vessels (as occurs in Mönckeberg arteriosclerosis with calcification of the arterial wall).

If the index is > 1.40 but suspicion of PAD remains high, a toe-brachial index and toe pressure are performed to check for arterial stenoses or occlusions. Ischemic lesions are unlikely to heal when the toe systolic BP is < 30 mm Hg, while healing potential is considered likely if toe pressure is > 60 mm Hg.

Lower extremity PAD and the likelihood of ulcer healing can also be assessed by transcutaneous oximetry (TcO2). A TcO2 level < 40 mm Hg (5.32 kPa) is predictive of poor healing, and a value < 20 mm Hg (2.66 kPa) is consistent with chronic limb-threatening ischemia.

Angiography provides details of the location and extent of arterial stenoses or occlusions; it is a prerequisite for endovascular and/or surgical revascularization procedures. It is not a substitute for noninvasive testing because it provides no information about the functional significance of abnormal findings. Arterial duplex ultrasound, magnetic resonance angiography, and CT angiography are noninvasive testing options that can facilitate planning for invasive angiography and help plan for revascularization (1, 2).

Diagnosis references

1. Gornik HL, Aronow HD, Goodney PP, et al. 2024 ACC/AHA/AACVPR/APMA/ABC/SCAI/SVM/SVN/SVS/SIR/VESS Guideline for the Management of Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Circulation 2025 Apr 8;151(14):e918. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001329]. Circulation 2024;149(24):e1313-e1410. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001251

2. Mazzolai L, Teixido-Tura G, Lanzi S, et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of peripheral arterial and aortic diseases. Eur Heart J 2024;45(36):3538-3700. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehae179

Treatment of Peripheral Artery Disease

Risk factor management (eg, diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension)

Lifestyle modification (eg, exercise, smoking cessation, weight management)

Antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications

Cilostazol for claudicationCilostazol for claudication

Antihypertensive therapy with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs)

Endovascular or surgical revascularization for symptomatic disease

Preventive care

All patients require aggressive lifestyle and risk factor modification for relief of peripheral artery disease symptoms and prevention of cardiovascular disease, including:

Smoking cessation, which is essential

Control of diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension

Structured exercise therapy

Dietary changes

Both supervised and home-based exercise training are recommended for patients with lower extremity PAD (1, 2). Approximately 30 to 60 minutes of treadmill or track walking in an exercise-rest-exercise pattern is recommended at least 3 times per week. Supervised exercise programs are probably superior to home-based exercise programs. Exercise can increase symptom-free walking distance and improve quality of life. Mechanisms probably include increased collateral circulation, improved endothelial function with microvascular vasodilation, decreased blood viscosity, improved red blood cell filterability, decreased ischemia-induced inflammation, and improved oxygen extraction.

Preventive foot care is crucial, especially for patients with diabetes. It includes daily foot inspection for injuries and skin breakdown; treatment of calluses and corns by a podiatrist; daily washing of the feet in lukewarm water with mild soap, followed by gentle, thorough drying; and avoidance of thermal, chemical, and mechanical injury, especially that due to poorly fitting footwear. Foot ulcer management is discussed elsewhere.

Pharmacotherapy

Statins, ACE inhibitors or ARBs, and aspirin are given to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events (see Treatment of Atherosclerosis).

Antiplatelet monotherapy is recommended for all patients with lower extremity PAD who have symptoms (3, 4). Antiplatelet medications may modestly lessen symptoms and increase walking distance in patients with PAD; more importantly, these medications modify atherogenesis and help prevent acute coronary syndromes and transient ischemic attacks. Options for patients with symptomatic PAD include aspirin or clopidogrel orally. Randomized trials have shown that the combination of rivaroxaban and orally. Randomized trials have shown that the combination of rivaroxaban andaspirin reduced cardiovascular events, including death, and major adverse limb events, including amputation (5, 6). Some data, however, suggest that the combination of aspirin plus rivaroxaban 2.5 mg orally 2 times a day also increases the risk of bleeding (7).

Cilostazol taken orally may be used to relieve intermittent claudication by improving blood flow and enhancing tissue oxygenation in affected areas; however, Cilostazol taken orally may be used to relieve intermittent claudication by improving blood flow and enhancing tissue oxygenation in affected areas; however,cilostazol is not a substitute for risk factor modification and exercise. The most common adverse effects of cilostazol are headache and diarrhea. Cilostazol is contraindicated in patients with systolic heart failure.

ACE inhibitors and ARBs have several beneficial effects. They are antiatherogenic and are potent vasodilators. Among patients undergoing vascular intervention for chronic limb-threatening ischemia, those on ACE inhibitors or ARBs had improved amputation-free and overall survival (8). Beta-blockers are also safe in patients with lower extremity PAD (3).

Other medications that may relieve claudication are being studied but are not available in the United States; they include L-arginine (the precursor of endothelium-dependent vasodilator), nitric oxide, vasodilator prostaglandins, chelation therapy, and angiogenic growth factors (eg, vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF], basic fibroblast growth factor [bFGF]) ((the precursor of endothelium-dependent vasodilator), nitric oxide, vasodilator prostaglandins, chelation therapy, and angiogenic growth factors (eg, vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF], basic fibroblast growth factor [bFGF]) (4, 9).

Endovascular revascularization

Endovascular revascularization has advanced significantly over the past few decades. The use of multiple modalities in endovascular revascularization, including percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA), atherectomy, and/or stenting, has been proven to improve durability and intermediate- and long-term clinical outcomes. Success for patients undergoing endovascular revascularization is quite high (procedural success> 90%, 3-year patency 58 to 82% depending on type and location of stent) (10, 11). More than 80% of all patients undergoing revascularization undergo endovascular revascularization as the first-line treatment (12).

Indications for endovascular revascularization include:

Intermittent claudication that limits daily activities and does not respond to risk factor modification and noninvasive treatments

Rest pain

Ischemic ulceration or tissue loss

Gangrene

Complications of endovascular revascularization include thrombosis at the site of dilation, distal embolization, vessel dissection, vessel perforation, and bleeding complications.

Studies have shown similar limb salvage rates in patients undergoing endovascular and surgical revascularization (13, 14), and patient preferences and patient risk should be considered prior to embarking on either endovascular or surgical revascularization.

Surgical revascularization

Surgical revascularization is indicated for patients:

Who can safely tolerate a major vascular procedure

With acute limb ischemia

With chronic limb-threatening ischemia

With symptomatic intermittent claudication that does not respond to noninvasive treatments (eg, similar to the indications for endovascular revascularization)

The goal is to relieve symptoms, prevent or decrease tissue loss, and avoid amputation. While some patients are at high risk for acute coronary syndrome and other complications of surgical revascularization, the empiric use of coronary revascularization is not recommended prior to vascular surgery.

Thromboendarterectomy (surgical removal of an occlusive lesion) is used for short, localized lesions in the aortoiliac, common femoral, and/or deep femoral arteries.

Lower extremity bypass (eg, femoropopliteal bypass grafting) uses synthetic or natural materials (often the saphenous or another vein) to bypass occlusive lesions. Lower extremity bypass is often used to prevent limb amputation and relieve claudication.

Sympathectomy may be effective in patients who cannot undergo major vascular surgery, when a distal occlusion causes severe ischemic pain. Chemical sympathetic blocks are as effective as surgical sympathectomy, so the latter is rarely performed.

Amputation is a procedure of last resort, indicated for uncontrolled infection, unrelenting rest pain, and progressive gangrene. Amputation should be as distal as possible, preserving knee and ankle function (if possible) to permit ongoing ambulation. If more severe PAD is present, below knee amputation is preferred over above knee amputation so that patients can be considered for limb prosthesis after amputation (8).

Treatment references

1. McDermott MM, Liu K, Guralnik JM, et al. Home-based walking exercise intervention in peripheral artery disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013;310(1):57-65. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.7231

2. Treat-Jacobson D, McDermott MM, Bronas UG, et al. Optimal Exercise Programs for Patients With Peripheral Artery Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019;139(4):e10-e33. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000623

3. Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al: 2016 AHA/ACC Guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease. Circulation 155:e686–e725, 2017.

4. Gornik HL, Aronow HD, Goodney PP, et al. 2024 ACC/AHA/AACVPR/APMA/ABC/SCAI/SVM/SVN/SVS/SIR/VESS Guideline for the Management of Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Circulation 2025 Apr 8;151(14):e918. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001329]. Circulation 2024;149(24):e1313-e1410. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001251

5. Anand S, Bosch J, Eikelboom JW, et al, on behalf of the COMPASS Investigators: Rivaroxaban with or without aspirin in patients with stable peripheral or carotid artery disease: an international, randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Lancet 391(10117):218–229, 2018. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32409-1

6. Bonaca MP, Bauersachs RM, Anand SS, et al: Rivaroxaban in peripheral artery disease after revascularization. N Engl J Med 382:1994–2004, 2020. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2000052

7. Hiatt WR, Bonaca MP, Patel MR, et al. Rivaroxaban and Aspirin in Peripheral Artery Disease Lower Extremity Revascularization. Circulation142 (23):2219-2230, 2020. doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.050465

8. Khan SZ, O'Brien-Irr MS, Rivero M, et al. Improved survival with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers in chronic limb-threatening ischemia. J Vasc Surg 2020;72(6):2130-2138. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2020.02.041

9. Mazzolai L, Teixido-Tura G, Lanzi S, et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of peripheral arterial and aortic diseases. Eur Heart J 2024;45(36):3538-3700. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehae179

10. Farber A. Chronic Limb-Threatening Ischemia. N Engl J Med 2018;379(2):171-180. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1709326

11. Kullo IJ, Rooke TW. CLINICAL PRACTICE. Peripheral Artery Disease. N Engl J Med 2016;374(9):861-871. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1507631

12. Guez D, Hansberry DR, Gonsalves CF, et al. Recent Trends in Endovascular and Surgical Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Disease in the Medicare Population. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2020;214(5):962-966. doi:10.2214/AJR.19.21967

13. Bradbury AW, Moakes CA, Popplewell M, et al. A vein bypass first versus a best endovascular treatment first revascularisation strategy for patients with chronic limb threatening ischaemia who required an infra-popliteal, with or without an additional more proximal infra-inguinal revascularisation procedure to restore limb perfusion (BASIL-2): an open-label, randomised, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2023;401(10390):1798-1809. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00462-2

14. Farber A, Menard MT, Conte MS, et al. Surgery or Endovascular Therapy for Chronic Limb-Threatening Ischemia. N Engl J Med 2022;387(25):2305-2316. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2207899

Key Points

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) occurs most frequently in the lower extremities.

Most patients also have significant cerebral or coronary atherosclerosis or both.

When symptomatic, PAD causes intermittent claudication, which is discomfort in the legs that occurs during walking and is relieved by rest; it is a manifestation of exercise-induced reversible ischemia, similar to angina pectoris.

More severe perfusion abnormalities in PAD may cause ischemic rest pain, ischemic ulcers, or gangrene of the toes or elsewhere on the feet.

A low (≤ 0.90) ankle-brachial index (ratio of ankle to arm systolic blood pressure) is diagnostic of lower extremity PAD.

Modify atherosclerosis risk factors; give statins, antiplatelet medications, and sometimes angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, rivaroxaban, or cilostazol.Modify atherosclerosis risk factors; give statins, antiplatelet medications, and sometimes angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, rivaroxaban, or cilostazol.

Endovascular revascularization and surgical revascularization are both options for patients with symptomatic lower extremity PAD.