Postpartum hemorrhage is blood loss of > 1000 mL or blood loss accompanied by symptoms or signs of hypovolemia within 24 hours after childbirth. Diagnosis is clinical. Treatment depends on etiology of the hemorrhage.

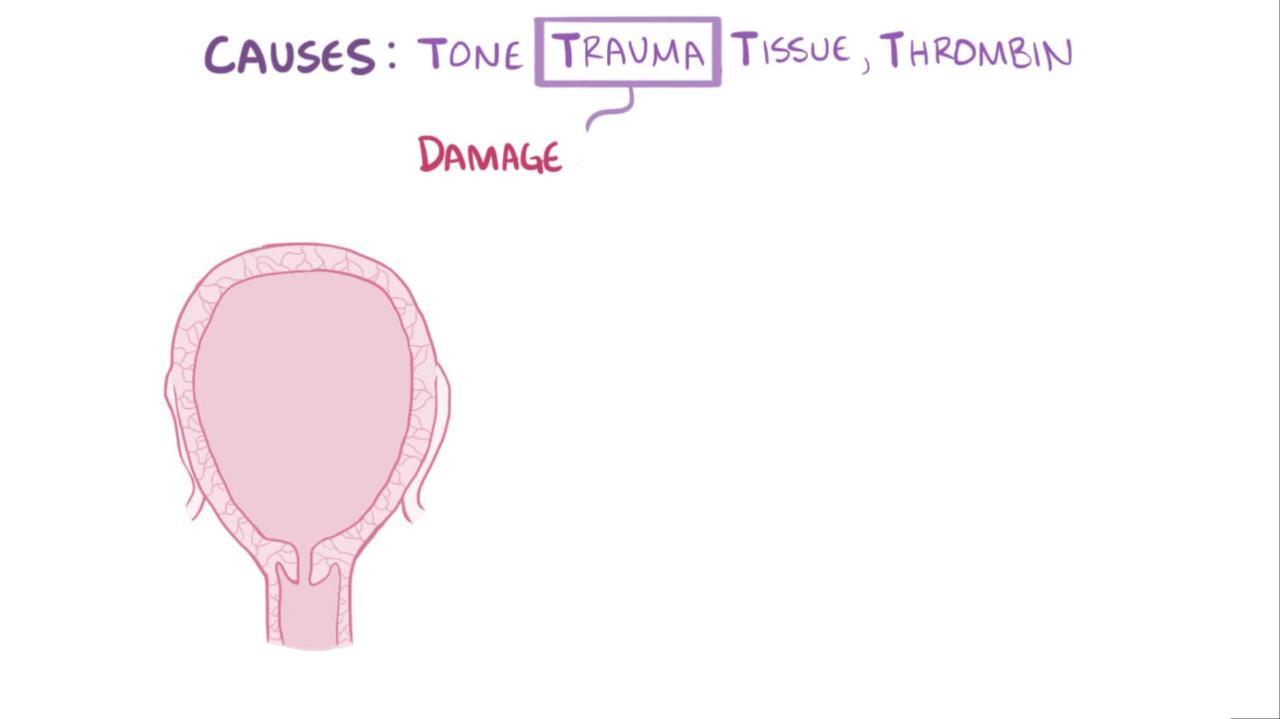

Etiology of Postpartum Hemorrhage

The most common cause of postpartum hemorrhage is

Uterine atony

Risk factors for uterine atony include

Uterine overdistention (caused by multifetal pregnancy, polyhydramnios, fetal anomaly, or an abnormally large fetus)

Prolonged labor or dysfunctional labor

Grand multiparity (delivery of ≥ 5 viable fetuses)

Relaxant anesthetics

Rapid labor

Intra-amniotic infection (chorioamnionitis)

Other causes of postpartum hemorrhage include

Lacerations of the genital tract

Extension of an episiotomy

Retained placental tissues

Hematoma

Intra-amniotic infection

Subinvolution (incomplete involution) of the placental site (which usually occurs early but may occur as late as 1 month after delivery)

Uterine fibroids may contribute to postpartum hemorrhage. A history of postpartum hemorrhage may indicate increased risk.

Diagnosis of Postpartum Hemorrhage

Clinical estimate of blood loss

Monitoring vital signs

There are various assessment tools (eg, checklists) to help obstetric practitioners and health care facilities develop ways to rapidly recognize and manage postpartum hemorrhage (1, 2). These tools are widely available and can be adjusted to suit the needs of the specific patient population.

Diagnosis references

1. California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative Hemorrhage Task Force: OB hemorrhage toolkit V 2.0. Accessed November 2, 2023

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics: Practice Bulletin No. 183: Postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol 130:e168–186, 2017. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002351

Treatment of Postpartum Hemorrhage

Fluid resuscitation and sometimes transfusion

Uterine massage

Removal of retained placental tissue

Repair of genital tract lacerations

Uterotonics (eg, oxytocin, prostaglandins, methylergonovine)Uterotonics (eg, oxytocin, prostaglandins, methylergonovine)

Sometimes surgical procedures

Intravascular volume is replenished with 0.9% saline up to 2 L IV; blood transfusion is used if this volume of saline is inadequate.

Procedure by Kate Barrett, MD and Will Stone, MD, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center Residency in Obstetrics and Gynecology; Barton Staat, MD, Uniformed Services University; and Shad Deering, COL, MD, Chair, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center Residency in Obstetrics and Gynecology; Assisted by Elizabeth N Weissbrod, MA, CMI, Eric Wilson, 2LT, and Jamie Bradshaw at the Val G. Hemming Simulation Center at the Uniformed Services University.

Procedure by Kate Leonard, MD, and Will Stone, MD, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center Residency in Obstetrics and Gynecology; and Shad Deering, COL, MD, Chair, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Uniformed Services University. Assisted by Elizabeth N. Weissbrod, MA, CMI, Eric Wilson, 2LT, and Jamie Bradshaw at the Val G. Hemming Simulation Center at the Uniformed Services University.

Procedure by Kate Barrett, MD and Will Stone, MD, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center Residency in Obstetrics and Gynecology; Barton Staat, MD, Uniformed Services University; and Shad Deering, COL, MD, Chair, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Uniformed Services University and Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. Assisted by Elizabeth N Weissbrod, MA, CMI, Eric Wilson, 2LT, and Jamie Bradshaw at the Val G. Hemming Simulation Center at the Uniformed Services University.

Hemostasis is attempted by bimanual uterine massage and IV oxytocin infusion. A dilute oxytocin IV infusion (10 or 20 [up to 80] units/1000mL of IV fluid) at 125 to 200 mL/hour is given immediately after delivery of the placenta. The drug is continued until the uterus is firm; then it is decreased or stopped. Oxytocin should not be given as an IV bolus because severe hypotension may occur.Hemostasis is attempted by bimanual uterine massage and IV oxytocin infusion. A dilute oxytocin IV infusion (10 or 20 [up to 80] units/1000mL of IV fluid) at 125 to 200 mL/hour is given immediately after delivery of the placenta. The drug is continued until the uterus is firm; then it is decreased or stopped. Oxytocin should not be given as an IV bolus because severe hypotension may occur.

In addition, the uterus is explored for lacerations and retained placental tissues. The cervix and vagina are also examined; lacerations are repaired. Bladder drainage via catheter can sometimes reduce uterine atony.

15-Methyl prostaglandin F2-alpha 250 mcg IM every 15 to 90 minutes up to 8 doses or methylergonovine 0.2 mg IM every 2 to 4 hours (which may be followed by 0.2 mg orally 3 to 4 times a day for 1 week) should be tried if excessive bleeding continues during oxytocin infusion; during cesarean delivery, these drugs may be injected directly into the myometrium. Oxytocin 10 units can also be directly injected into the myometrium. If oxytocin is not available, heat-stable carbetocin can be given IM instead. Prostaglandins should be avoided in women with asthma; methylergonovine should be avoided in women with hypertension. Sometimes misoprostol 800 to 1000 mcg rectally can be used to increase uterine tone.15-Methyl prostaglandin F2-alpha 250 mcg IM every 15 to 90 minutes up to 8 doses or methylergonovine 0.2 mg IM every 2 to 4 hours (which may be followed by 0.2 mg orally 3 to 4 times a day for 1 week) should be tried if excessive bleeding continues during oxytocin infusion; during cesarean delivery, these drugs may be injected directly into the myometrium. Oxytocin 10 units can also be directly injected into the myometrium. If oxytocin is not available, heat-stable carbetocin can be given IM instead. Prostaglandins should be avoided in women with asthma; methylergonovine should be avoided in women with hypertension. Sometimes misoprostol 800 to 1000 mcg rectally can be used to increase uterine tone.

Uterine packing or placement of a Bakri balloon can sometimes provide tamponade. This silicone balloon can hold up to 500 mL and withstand internal and external pressures of up to 300 mm Hg. If hemostasis cannot be achieved, surgical placement of a B-Lynch suture (a suture used to compress the lower uterine segment via multiple insertions), hypogastric artery ligation, or hysterectomy may be required. Uterine rupture requires surgical repair.

An intrauterine vacuum-induced hemorrhage-control device may be used. It applies low-level suction to induce uterine contractions, causing the uterus to collapse on itself; as a result, blood vessels in the myometrium constrict and hemorrhage is rapidly stopped (1). The device consists of an intrauterine loop, an expandable seal that is filled with sterile fluid and blocks the cervix to maintain the vacuum, and a vacuum connector attached to a tube that connects with a vacuum source. Suction is applied for 1 hour after bleeding is controlled.

Blood products are transfused as necessary, depending on the degree of blood loss and clinical evidence of shock. Massive transfusion of packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, and platelets in a 1:1:1 ratio can be considered after consultation with the blood bank (2).

Tranexamic acid can also be used if initial medical management is ineffective (1 g IV over 10 minutes).Tranexamic acid can also be used if initial medical management is ineffective (1 g IV over 10 minutes).

Treatment reference

1. D’Alton ME, Rood KM, Smid M C, et al: Intrauterine vacuum-induced hemorrhage-control device for rapid treatment of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol 136 (5):1–10, 2020. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004138

Prevention of Postpartum Hemorrhage

Predisposing conditions (eg, uterine fibroids, polyhydramnios, multifetal pregnancy, a maternal bleeding disorder, history of puerperal hemorrhage or postpartum hemorrhage) are identified antepartum and, when possible, corrected.

If women have an unusual blood type, blood available for transfusion appropriate for that blood type is made available ahead of time. Careful, unhurried delivery with a minimum of intervention is always wise.

After placental separation, oxytocin 10 units IM or dilute oxytocin infusion (10 or 20 units in 1000 mL of an IV solution at 125 to 200 mL/hour for 1 to 2 hours) usually ensures uterine contraction and reduces blood loss.After placental separation, oxytocin 10 units IM or dilute oxytocin infusion (10 or 20 units in 1000 mL of an IV solution at 125 to 200 mL/hour for 1 to 2 hours) usually ensures uterine contraction and reduces blood loss.

After the placenta is delivered, it is thoroughly examined for completeness; if it is incomplete, the uterus is manually explored and retained fragments are removed. Rarely, curettage is required.

Uterine contraction and amount of vaginal bleeding must be observed for 1 hour after completion of the third stage of labor.

Key Points

Before delivery, assess risk of postpartum hemorrhage, including identification of antenatal risk factors (eg, bleeding disorders, multifetal pregnancy, polyhydramnios, an abnormally large fetus, grand multiparity).

Postpartum hemorrhage assessment tools are widely available and can be adjusted for the specific patient population.

Replenish intravascular volume, repair genital lacerations, and remove retained placental tissues.

Massage the uterus and, if necessary, use uterotonics (eg, oxytocin, prostaglandins, methylergonovine).Massage the uterus and, if necessary, use uterotonics (eg, oxytocin, prostaglandins, methylergonovine).

If hemorrhage persists, consider use of an intrauterine vacuum device, intrauterine balloon tamponade, packing, surgical procedures, and transfusion of blood products.

For women at risk, deliver slowly and without unnecessary interventions.