Topic Resources

The lifetime prevalence of bulimia nervosa is approximately 0.5% of women and 0.1% of men (1). Those affected are persistently and overly concerned about body shape and weight. Unlike patients with anorexia nervosa, those with bulimia nervosa are of normal or above-normal weight.

Bulimia nervosa, like anorexia nervosa, appears more likely to develop in cultures favoring a thin ideal (2, 3). In addition, participation in activities emphasizing body shape or weight (eg, gymnastics, ballet) have been associated with the development of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa (4).

General references

1. Udo T, Grilo CM. Prevalence and correlates of DSM-5–defined eating disorders in a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults. Biol Psychiatry. 1;84(5):345-354, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.03.014.

2. van Eeden AE, van Hoeken D, Hoek HW. Incidence, prevalence and mortality of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2021;34(6):515-524. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000739

3. Akoury LM, Warren CS, Culbert KM. Disordered Eating in Asian American Women: Sociocultural and Culture-Specific Predictors. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1950. Published 2019 Sep 4. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01950

4. Attia E, Walsh BT. Eating Disorders: A Review. JAMA. 2025;333(14):1242-1252. doi:10.1001/jama.2025.0132

Symptoms and Signs of Bulimia Nervosa

Patients with bulimia nervosa typically describe binge-purge behavior. Binges involve rapid consumption of an amount of food definitely larger than most people would eat in a similar period of time under similar circumstances (however, the amount considered excessive for a normal meal versus a holiday meal may differ) accompanied by feelings of loss of control.

Patients tend to consume sweet, high-fat foods (eg, ice cream, cake) during binge episodes. The amount of food consumed in a binge varies, sometimes involving thousands of calories. Binges tend to be episodic, are often triggered by psychosocial stress, may occur as often as several times a day, and are usually carried out in secret.

Binge eating is followed by compensatory behaviors: self-induced vomiting, use of laxatives or diuretics, excessive exercise, and/or fasting.

Patients are typically of normal weight; only a minority have excess weight or obesity. However, patients are excessively concerned about their body weight and/or shape; they are often dissatisfied with their bodies and think that they need to lose weight.

Patients with bulimia nervosa tend to be more aware of and remorseful or guilty about their behaviors than those with anorexia nervosa and are more likely to acknowledge their concerns when questioned by a sympathetic clinician. They are also less socially isolated and more prone to impulsive behavior, drug and alcohol use disorders, and overt depression. Depression, anxiety (eg, concerning weight and/or social situations) and anxiety disorders are common among these patients.

Most physical signs of bulimia nervosa result from purging. Self-induced vomiting may lead to erosion of dental enamel of the front teeth, painless parotid (salivary) gland enlargement, and an inflamed esophagus. Physical signs include the following:

Swollen parotid glands

Scars on the back of the hand (from repeatedly inducing vomiting by using fingers to trigger gag reflex)

Dental erosion

Complications

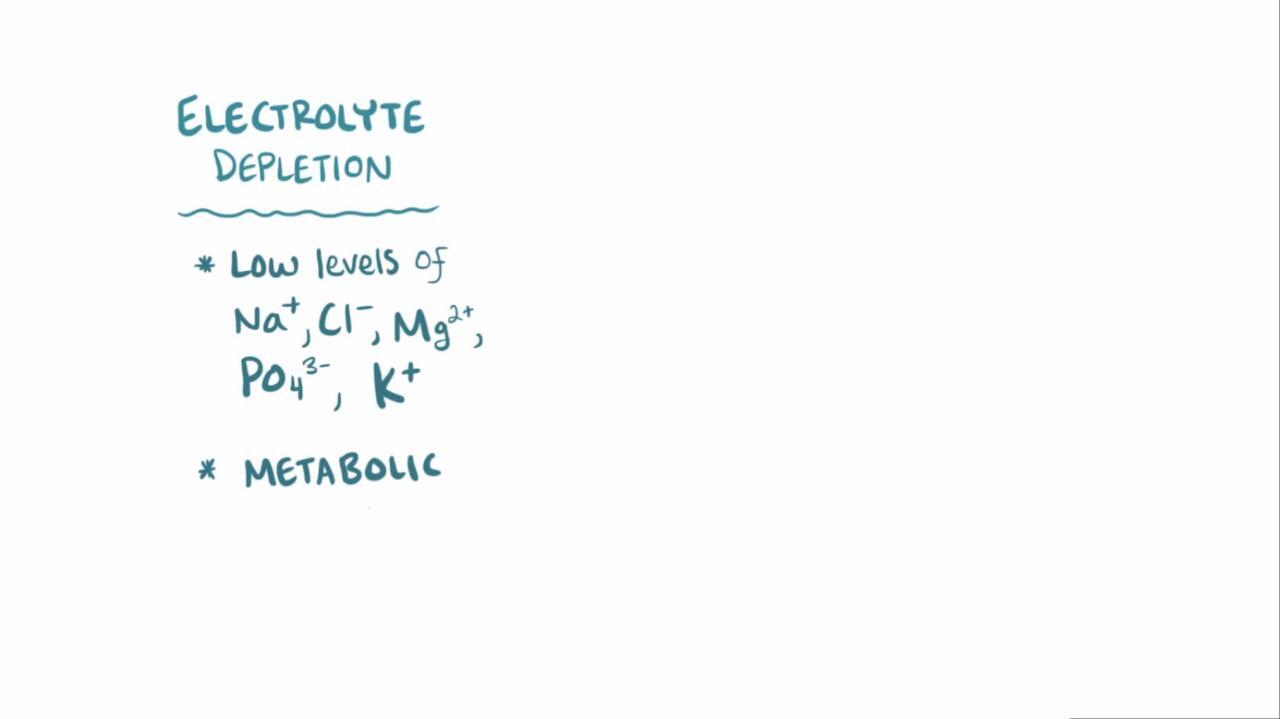

Serious fluid and electrolyte disturbances, especially hypokalemia, occur occasionally. Extremely rarely, the stomach ruptures or the esophagus is torn during a binge or purge episode, leading to life-threatening complications (1).

Because substantial weight loss does not occur, other serious complications that often occur with anorexia nervosa are not present. However, cardiomyopathy may result from long-term use of syrup of ipecac to induce vomiting (2).

Complications references

1. Uniacke B, Walsh BT. Eating Disorders. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(8):ITC113-ITC128. doi:10.7326/AITC202208160

2. Silber TJ. Ipecac syrup abuse, morbidity, and mortality: isn't it time to repeal its over-the-counter status?. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37(3):256-260. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.022

Diagnosis of Bulimia Nervosa

Psychiatric assessment

Sometimes laboratory tests

Clinical criteria for diagnosis of bulimia nervosa from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR) include the following (1):

Recurrent episodes of binge eating (the uncontrolled consumption of unusually large amounts of food) that are accompanied by feelings of loss of control over eating and that occur, on average, at least once a week for 3 months

Recurrent inappropriate compensatory behavior to influence body weight (on average, at least once a week for 3 months)

Self-evaluation that is unduly influenced by body shape and weight concerns

Laboratory measurement of electrolytes can identify abnormalities, particularly hypokalemia (2).

Diagnosis references

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed, Text Revision. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2022:387-392.

2. Wolfe BE, Metzger ED, Levine JM, Jimerson DC. Laboratory screening for electrolyte abnormalities and anemia in bulimia nervosa: a controlled study. Int J Eat Disord. 2001;30(3):288-293. doi:10.1002/eat.1086

Treatment of Bulimia Nervosa

Cognitive behavioral therapy

Interpersonal psychotherapy

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

Cognitive behavioral therapy is the treatment of choice for bulimia nervosa (1–3). Therapy usually involves 16 to 20 individual sessions over 4 to 5 months, although it can also be done as group therapy. Treatment aims to

Increase motivation for change

Replace dysfunctional eating with a regular and flexible pattern

Decrease undue concern with body shape and weight

Prevent relapse

Cognitive behavioral therapy eliminates binge eating and purging in approximately 35 to 50% of patients (4, 5). Many others show improvement; some drop out of treatment or do not respond. Improvement is usually well maintained over the long-term.

In interpersonal psychotherapy, the emphasis is on helping patients identify and alter current interpersonal problems that may be maintaining the eating disorder. The treatment is both nondirective and noninterpretive and does not focus directly on eating disorder symptoms. Interpersonal psychotherapy can be considered an alternative when cognitive behavioral therapy is unavailable.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors used alone do reduce the frequency of binge eating and vomiting but are not ideal as a sole treatment without psychotherapy (3, 6, 7). SSRIs are also effective in treating comorbid anxiety and depression. Fluoxetine is often used for the treatment of bulimia nervosa in adults, at a dose higher than that typically used for depression in adults (). SSRIs are also effective in treating comorbid anxiety and depression. Fluoxetine is often used for the treatment of bulimia nervosa in adults, at a dose higher than that typically used for depression in adults (2).

Treatment references

1. Grilo CM. Treatment of Eating Disorders: Current Status, Challenges, and Future Directions. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2024;20(1):97-123. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-080822-043256

2. Crone C, Fochtmann LJ, Attia E, et al. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Eating Disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2023;180(2):167-171. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.23180001

3. National Guideline Alliance (UK). Eating Disorders: Recognition and Treatment. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); May 2017.

4. Linardon J, Wade TD. How many individuals achieve symptom abstinence following psychological treatments for bulimia nervosa? A meta-analytic review. Int J Eat Disord. 2018;51(4):287-294. doi:10.1002/eat.22838

5. Waller G, Gray E, Hinrichsen H, Mountford V, Lawson R, Patient E. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa and atypical bulimic nervosa: effectiveness in clinical settings. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47(1):13-17. doi:10.1002/eat.22181

6. Bacaltchuk J, Hay P. Antidepressants versus placebo for people with bulimia nervosa. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;2003(4):CD003391. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003391

7. Argyrou A, Lappas AS, Bakaloudi DR, et al. Pharmacotherapy compared to placebo for people with Bulimia Nervosa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2023;327:115357. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115357

Key Points

Bulimia nervosa involves recurrent episodes of binge eating followed by inappropriate compensatory behavior such as self-induced vomiting, laxative or diuretic abuse, fasting, or excessive exercise.

Unlike patients with anorexia nervosa, patients rarely lose much weight or develop nutritional deficiencies.

Recurrent self-induced vomiting may erode dental enamel and/or cause esophagitis.

Serious fluid and electrolyte disturbances, especially hypokalemia, occur occasionally.

Rupture of the esophagus or stomach or cardiomyopathy are rare complications.

Treat with cognitive behavioral therapy and sometimes an SSRI.

Drugs Mentioned In This Article