Topic Resources

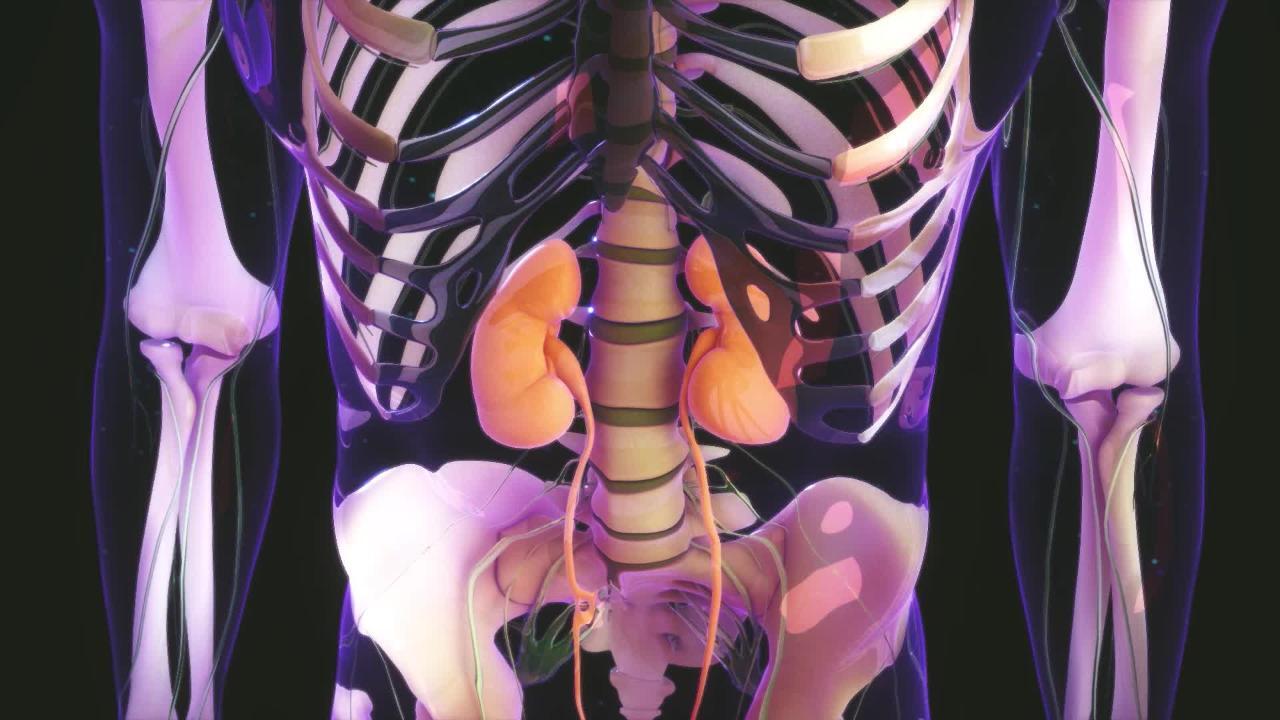

Most solid kidney tumors are cancerous, but purely fluid-filled tumors (cysts) generally are not. Almost all kidney cancer is renal cell carcinoma. Another kind of kidney cancer, Wilms tumor, occurs primarily in children.

Kidney cancer may cause blood in the urine, pain in the side, or fever.

Cancer is most often detected by accident when an imaging test is done for another reason.

Diagnosis is by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging.

Removing the kidney prolongs survival and may be curative if cancer has not spread.

Kidney cancer accounts for about 2 to 3% of cancers in adults, affecting about twice as many men as women. About 81,610 people develop kidney cancer each year, and about 14,390 die of it (2024 estimates).

People who smoke are about twice as likely to develop kidney cancer as people who do not smoke. Other risk factors include exposure to toxic chemicals (for example, asbestos, cadmium, and leather tanning and petroleum products) and obesity. People who are undergoing dialysis and develop cystic kidney disease and people with certain inherited disorders (particularly von Hippel–Lindau disease [VHL] and tuberous sclerosis complex) are also at higher risk of kidney cancer. People with kidney cancer are usually diagnosed between 65 and 74 years of age.

Symptoms of Kidney Cancer

Symptoms may not occur until the cancer has spread (metastasized) or become very large. Blood in the urine is the most common first symptom, but the amount of blood may be so small that it can be detected only under a microscope. On the other hand, the urine may be visibly red.

The next most common symptoms are pain in the area between the ribs and hip (the flank), fever, and weight loss. Infrequently, a kidney cancer is first detected when a doctor feels an enlargement or lump in the abdomen. Nonspecific symptoms of kidney cancer include fatigue, weight loss, and early satiety (feeling of fullness after a meal).

The red blood cell count may become abnormally high (polycythemia) because high levels of the hormone erythropoietin (which is produced by the diseased kidney or by the tumor itself) stimulate the bone marrow to increase the production of red blood cells. Symptoms of a high red blood cell count may be absent or may include headache, fatigue, dizziness, and vision disturbances. Conversely, kidney cancer may lead to a drop in the red blood cell count (anemia) because of slow bleeding into the urine. Anemia may cause easy fatigability or dizziness.

Some people develop high levels of calcium in the blood (hypercalcemia), which may cause weakness, fatigue, slowed reaction times, and constipation.

Blood pressure may increase, but high blood pressure may not cause symptoms.

Diagnosis of Kidney Cancer

Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Sometimes surgery

Most kidney cancers are discovered by chance when an imaging test, such as CT or ultrasound, is done to evaluate another problem, such as high blood pressure. If doctors suspect kidney cancer based on a person’s symptoms, they use CT or MRI to confirm the diagnosis. Ultrasonography or intravenous urography may also be used initially, but doctors use CT or MRI to verify the diagnosis.

If cancer is diagnosed, other imaging tests (for example, chest x-ray, bone scan, or CT of the chest) as well as blood tests may be done to determine whether and where the cancer has spread. However, sometimes cancer that has recently spread (metastasized) cannot be detected. Occasionally, surgery is needed to confirm the diagnosis. Rarely, doctors recommend a biopsy of either the kidney mass or other areas of the body that are suspected of having metastases to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment of Kidney Cancer

Surgery

When the cancer has not spread beyond the kidney, surgically removing the affected kidney provides a reasonable chance of cure. Alternatively, surgeons may remove only the tumor with a rim of adjacent normal tissue, which spares the remainder of the kidney. For very small masses in the kidney (smaller than 3 centimeters or about 1.2 inches), ablation (a procedure done by radiologists to burn or freeze the mass) may be an option. Active surveillance (close monitoring) may be an option for very small masses, typically in people too sick to tolerate surgery.

If the cancer has spread into adjacent sites, such as the renal vein or even the large vein that carries blood to the heart (vena cava), but has not spread to lymph nodes or distant sites, surgery may still provide a chance for cure. However, kidney cancer has a tendency to spread early, especially to the lungs, sometimes before symptoms develop. Because kidney cancer that has spread to distant sites may escape early diagnosis, metastasis sometimes becomes apparent only after doctors have surgically removed all of the kidney cancer that could be found.

If surgical cure seems unlikely, other treatments can be used, although these are rarely curative. Treating the cancer by enhancing the immune system’s ability to destroy it causes some cancers to shrink and may prolong survival (see Immunotherapy). Older immunotherapy treatments sometimes used for kidney cancer include interleukin-2 and interferon alfa-2b. Newer immunotherapies called checkpoint inhibitors block a molecule on cancer cells called PD-L1 (a "checkpoint"). PD-L1 can allow cancers to escape detection (and thus destruction) by the body's immune system. Combinations of medications that include checkpoint inhibitors are available. Often they are the treatment of choice in people with metastatic disease and after surgical resection of the cancer in people with intermediate to high risk of the cancer's recurrence.). Older immunotherapy treatments sometimes used for kidney cancer include interleukin-2 and interferon alfa-2b. Newer immunotherapies called checkpoint inhibitors block a molecule on cancer cells called PD-L1 (a "checkpoint"). PD-L1 can allow cancers to escape detection (and thus destruction) by the body's immune system. Combinations of medications that include checkpoint inhibitors are available. Often they are the treatment of choice in people with metastatic disease and after surgical resection of the cancer in people with intermediate to high risk of the cancer's recurrence.

Other medications sometimes used to treat kidney cancer include sunitinib, sorafenib, cabozantinib, axitinib, bevacizumab, pazopanib, lenvatinib, temsirolimus, and everolimus. These medications alter molecular pathways that affect the tumor and are thus called targeted therapies. Other medications sometimes used to treat kidney cancer include sunitinib, sorafenib, cabozantinib, axitinib, bevacizumab, pazopanib, lenvatinib, temsirolimus, and everolimus. These medications alter molecular pathways that affect the tumor and are thus called targeted therapies.

Various combinations of other interleukins, thalidomide, and even vaccines developed from cells removed from the kidney cancer are also being investigated. These treatments may be helpful for metastatic cancer, although the benefit is usually small. Rarely (in less than 1% of people), removing the affected kidney causes tumors elsewhere in the body to shrink. However, the slim possibility that tumor shrinkage will occur is not considered sufficient reason to remove a cancerous kidney when the cancer has already spread, unless removal is part of an overall plan that includes other treatments directed toward widespread cancer. Various combinations of other interleukins, thalidomide, and even vaccines developed from cells removed from the kidney cancer are also being investigated. These treatments may be helpful for metastatic cancer, although the benefit is usually small. Rarely (in less than 1% of people), removing the affected kidney causes tumors elsewhere in the body to shrink. However, the slim possibility that tumor shrinkage will occur is not considered sufficient reason to remove a cancerous kidney when the cancer has already spread, unless removal is part of an overall plan that includes other treatments directed toward widespread cancer.

Prognosis for Kidney Cancer

Many factors affect prognosis, but the 5-year survival rate for people with small cancers confined to the kidney is greater than 90%. Cancer that has spread has a much worse prognosis. In these people, the goal is often to focus on controlling the disease spread, pain relief, and other means to improve comfort (see Symptoms During a Fatal Illness). As with all terminal illnesses, planning for end-of-life issues (see Legal and Ethical Concerns), including creating advance directives, is essential.

Tumors Metastatic to the Kidney

Sometimes cancers in other areas of the body spread (metastasize) to the kidneys. Examples of such cancers include melanoma; cancers of the lung, breast, stomach, female reproductive organs, intestine, and pancreas; leukemia; and lymphoma.

Such spread usually does not cause symptoms. Spread is usually diagnosed when tests are done to determine how far the original cancer has spread. Treatment is usually directed at the original cancer. Occasionally, if the original cancer is treated and the tumor in the kidney is growing, the kidney tumor is removed.