(See also Acid-Base Regulation and Acid-Base Disorders.)

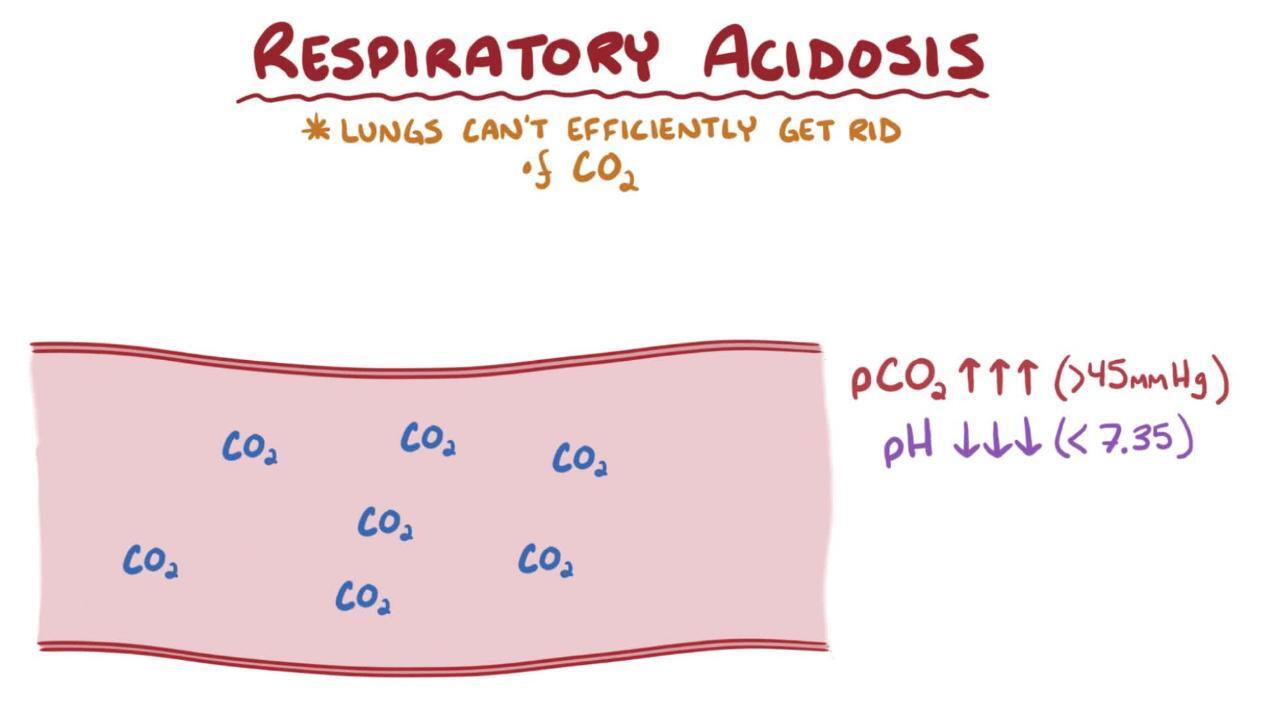

Respiratory acidosis is carbon dioxide (CO2) accumulation (hypercapnia) due to a decrease in respiratory rate and/or respiratory volume (hypoventilation). Causes of hypoventilation (discussed under Ventilatory Failure) include

Conditions that impair central nervous system (CNS) respiratory drive (eg, brain stem stroke, medications, drugs, or alcohol)

Conditions that impair neuromuscular transmission and other conditions that cause muscular weakness

Obstructive, restrictive, and parenchymal pulmonary disorders

Hypoxia typically accompanies hypoventilation.

Respiratory acidosis may be

Acute

Chronic

The distinction is based on the degree of metabolic compensation. In acute respiratory acidosis, hypoventilation causes the carbon dioxide to rise rapidly and blood pH to fall before effective buffering by the kidneys. Over the following 3 to 5 days, the kidneys increase bicarbonate reabsorption and hydrogen excretion significantly, returning blood pH toward, but not completely, to normal, transforming the acute respiratory acidoses into a chronic respiratory acidosis.

Symptoms and Signs of Respiratory Acidosis

Symptoms and signs depend on the rate and degree of Pco2 increase. CO2 rapidly diffuses across the blood-brain barrier. Symptoms and signs are a result of high CO2 concentrations and low pH in the CNS and any accompanying hypoxemia.

Acute (or acutely worsening chronic) respiratory acidosis causes headache, confusion, anxiety, drowsiness, and stupor (CO2 narcosis).

Chronic respiratory acidosis (as in COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease]) may be well tolerated, but patients may also have memory loss, sleep disturbances, excessive daytime sleepiness, and personality changes. Signs include gait disturbance, tremor, blunted deep tendon reflexes, myoclonic jerks, asterixis, and papilledema.

Diagnosis of Respiratory Acidosis

Arterial blood gas (ABG) and serum electrolyte measurements

Diagnosis of cause (usually clinical)

Recognition of respiratory acidosis and appropriate renal compensation (see Diagnosis of Acid-Base Disorders) requires ABG determination and measurement of serum electrolytes. Causes are usually obvious from history and examination.

Calculation of the alveolar-arterial (A-a) O2 gradient (inspired Po2 − [arterial Po2+5⁄4 arterial Pco2]) can help distinguish pulmonary from extrapulmonary disease; a normal gradient essentially excludes pulmonary disorders.

Treatment of Respiratory Acidosis

Adequate ventilation

Treatment is provision of adequate ventilation by either endotracheal intubation or noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (for specific indications and procedures, see Overview of Respiratory Failure). Adequate ventilation is all that is needed to correct respiratory acidosis. Chronic hypercapnia generally must be corrected slowly (eg, over several hours or more) because too-rapid Pco2 lowering can cause a posthypercapnic “overshoot” alkalosis when the underlying compensatory hyperbicarbonatemia becomes unmasked. The abrupt rise in CNS pH that results can lead to seizures and death.

Any potassium and chloride deficits are corrected.

Sodium bicarbonate is almost always contraindicatedSodium bicarbonate is almost always contraindicated because of the potential for paradoxical acidosis within the CNS. One exception may be in cases of severe bronchospasm, in which bicarbonate may improve responsiveness of bronchial smooth muscle to beta-agonists.

Key Points

Respiratory acidosis involves a decrease in respiratory rate and/or volume (hypoventilation).

Common causes include impaired respiratory drive (eg, due to drugs, medications, or CNS disease), and airflow obstruction (eg, due to asthma, COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease], sleep apnea, airway edema).

Recognize chronic hypoventilation by the presence of metabolic compensation (elevated bicarbonate [HCO3−]) and clinical signs of tolerance (less somnolence and confusion than expected for the degree of hypercarbia).

Treat the cause and provide adequate ventilation, using tracheal intubation or noninvasive positive pressure ventilation as needed.

Drugs Mentioned In This Article