Meniere disease is a disorder characterized by recurring attacks of disabling vertigo (a false sensation of moving or spinning), nausea, fluctuating hearing loss (in the lower frequencies), and noise in the ear (tinnitus).

Topic Resources

Symptoms include sudden, unprovoked attacks of severe, disabling vertigo, nausea, and vomiting, usually with a sensation of pressure in the ear and hearing loss.

Tests include hearing tests and sometimes magnetic resonance imaging.

A low-salt diet and a diuretic may lower the severity and frequency of attacks.

Medications such as meclizine or lorazepam may help relieve vertigo symptoms but will not prevent attacks.Medications such as meclizine or lorazepam may help relieve vertigo symptoms but will not prevent attacks.

Meniere disease is thought to be caused by an excess amount of the fluid that is normally present in the inner ear (see also Overview of the Inner Ear.) Fluid in the ear is held in a pouch-like structure called the endolymphatic sac. This fluid is continually being secreted and reabsorbed, maintaining a constant amount. Either an increase in production of inner ear fluid or a decrease in its reabsorption results in excess fluid. Why either happens is not known. This disease typically occurs in people between the ages of 20 and 50 years.

Symptoms of Meniere Disease

Symptoms of Meniere disease include sudden (acute), unprovoked attacks of severe, disabling vertigo and usually nausea and vomiting. Vertigo is a false sensation that people, their surroundings, or both are moving or spinning. Most people describe this unpleasant feeling as "dizziness," although people often also use the word "dizzy" for other sensations, such as being light-headed.

These symptoms usually last for 20 minutes to 12 hours. Rarely, they last up to 24 hours. Before and during an attack, a person often feels a fullness or pressure in the affected ear. Sometimes sounds seem unusually loud or distorted.

Hearing in the affected ear may be impaired after an attack of vertigo. Lower sound frequencies (hearing vowels) are harder to hear. Hearing tends to fluctuate but progressively worsens over the years.

Tinnitus, which some people describe as "ringing in the ear," may be constant or intermittent and may be worse before, during, or after an attack of vertigo.

Typically, only one ear is affected.

At first, symptoms may disappear between episodes. Symptom-free periods may last up to 1 year. However, as the disease progresses, hearing impairment gradually worsens, and tinnitus may become constant.

In one form of Meniere disease, hearing loss and tinnitus precede the first attack of vertigo by months or years. After the attacks of vertigo begin, hearing may improve.

Diagnosis of Meniere Disease

Hearing tests

Gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

A doctor suspects Meniere disease when the person has the typical symptoms of vertigo with tinnitus and hearing loss in one ear. Also, the vertigo is not triggered by changes in body position, unlike in people with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.

Doctors also use certain techniques to check for symptoms suggesting Meniere disease. For example, they may ask the person to focus on a target while they rotate the head to one side, then to the other and observe eye movements.

Doctors usually do hearing tests and sometimes gadolinium-enhanced MRI to look for other causes of the symptoms.

Prognosis for Meniere Disease

There is no proven way to stop hearing loss due to Meniere disease. Most people have moderate to severe hearing loss in the affected ear within 10 to 15 years.

Treatment of Meniere Disease

Preventing attacks by limiting salt, alcohol, and caffeine and taking a diuretic (water pill) Preventing attacks by limiting salt, alcohol, and caffeine and taking a diuretic (water pill)

Medications such as meclizine or lorazepam to relieve sudden attacks of vertigoMedications such as meclizine or lorazepam to relieve sudden attacks of vertigo

Medications such as prochlorperazine to relieve vomitingMedications such as prochlorperazine to relieve vomiting

Sometimes medications or surgery to reduce fluid pressure or destroy inner ear structures

Noninvasive treatments for Meniere disease

Following a low-salt diet, avoiding alcohol and caffeine, and taking a diuretic (such as hydrochlorothiazide or acetazolamide), that increases the excretion of urine) reduce the frequency of vertigo attacks in most people with Meniere disease. However, treatment may not stop the gradual hearing loss.Following a low-salt diet, avoiding alcohol and caffeine, and taking a diuretic (such as hydrochlorothiazide or acetazolamide), that increases the excretion of urine) reduce the frequency of vertigo attacks in most people with Meniere disease. However, treatment may not stop the gradual hearing loss.

When attacks do occur, vertigo may be relieved temporarily with medications given by mouth, such as meclizine or lorazepam. Nausea and vomiting may be relieved by pills or suppositories containing prochlorperazine. These medications do not help prevent attacks and thus should not be taken on a regular basis but only during acute spells of vertigo and nausea. To relieve symptoms, some doctors also give corticosteroids such as prednisone by mouth or sometimes an injection of the corticosteroid dexamethasone behind the eardrum. Certain medications used to prevent migraines (such as some antidepressants) help some people with Meniere disease.When attacks do occur, vertigo may be relieved temporarily with medications given by mouth, such as meclizine or lorazepam. Nausea and vomiting may be relieved by pills or suppositories containing prochlorperazine. These medications do not help prevent attacks and thus should not be taken on a regular basis but only during acute spells of vertigo and nausea. To relieve symptoms, some doctors also give corticosteroids such as prednisone by mouth or sometimes an injection of the corticosteroid dexamethasone behind the eardrum. Certain medications used to prevent migraines (such as some antidepressants) help some people with Meniere disease.

Invasive treatments for Meniere disease

Several procedures are available for people who are disabled by frequent attacks of vertigo despite noninvasive treatments. The procedures aim to reduce fluid pressure in the inner ear or destroy inner ear structures responsible for balance function. The least destructive of these procedures is called endolymphatic sac decompression. (The endolymphatic sac holds the fluid that surrounds the hair cells in the inner ear.) In this procedure, a surgeon makes an incision behind the ear and removes the bone over the endolymphatic sac so that it can be seen. A blade or laser is used to make a hole in the sac, thus allowing the fluid to drain. The surgeon may place a thin flexible plastic drain in the hole to help keep it open. This procedure does not affect people's balance and rarely harms hearing.

If endolymphatic sac decompression is ineffective, doctors may need to destroy the inner ear structures that are causing the symptoms by injecting a solution of gentamicin through the eardrum into the middle ear. Gentamicin selectively destroys balance function before affecting hearing, but hearing loss is still a risk. The risk of hearing loss is lower if doctors inject the gentamicin only once and wait 4 weeks before repeating if necessary. If endolymphatic sac decompression is ineffective, doctors may need to destroy the inner ear structures that are causing the symptoms by injecting a solution of gentamicin through the eardrum into the middle ear. Gentamicin selectively destroys balance function before affecting hearing, but hearing loss is still a risk. The risk of hearing loss is lower if doctors inject the gentamicin only once and wait 4 weeks before repeating if necessary.

People who still have frequent, severe episodes despite these treatments may need a more invasive surgical procedure. Cutting the vestibular nerve (vestibular neurectomy) permanently destroys the inner ear's ability to affect balance, usually preserves hearing, and successfully relieves vertigo in about 95% of people. This procedure is usually done to treat people whose symptoms do not lessen after endolymphatic sac decompression or people who never want to experience another spell of vertigo.

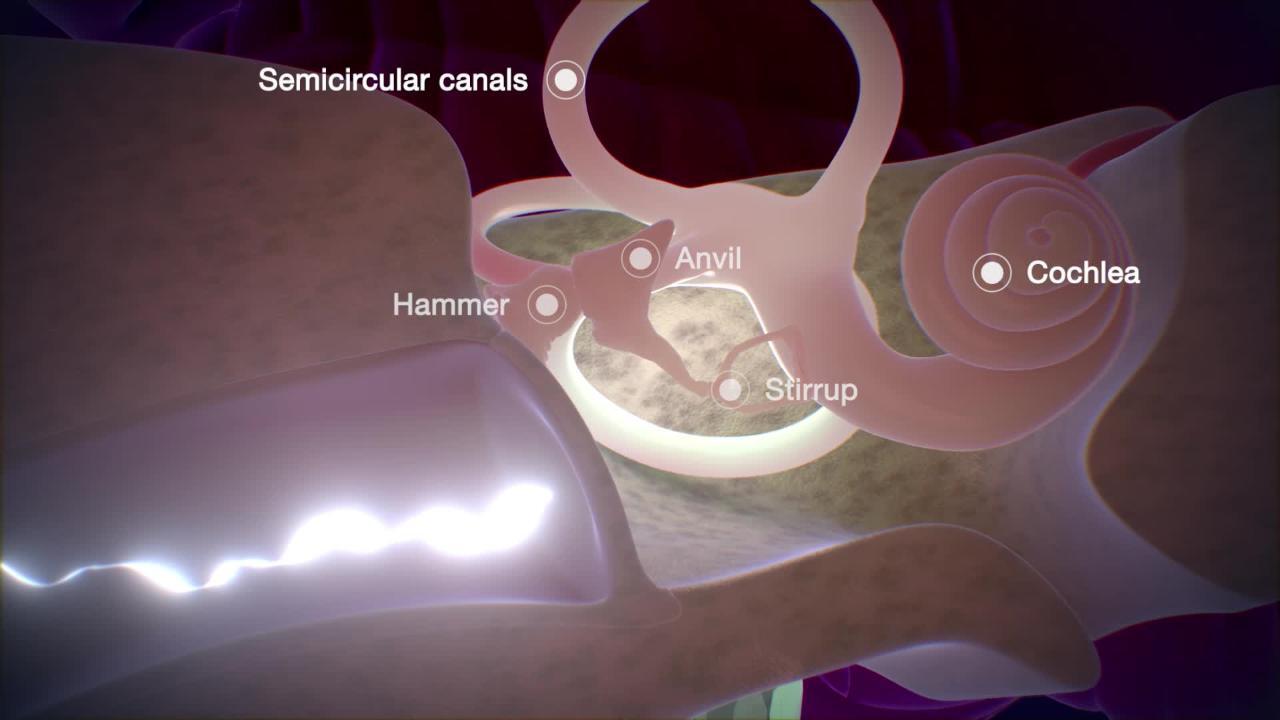

When vertigo is disabling and hearing has deteriorated in the involved ear, the semicircular canals can be removed in a procedure called a labyrinthectomy. Hearing restoration in these cases is sometimes possible with a cochlear implant.

None of the surgical procedures that treat vertigo are useful in treating the hearing loss that often accompanies Meniere disease.