Topic Resources

(See also Overview of Congenital Gastrointestinal Anomalies.)

The worldwide incidence of biliary atresia is approximately 1 in 5,000 to 20,000 live births; the highest incidence is in Asia (1, 2). The incidence in the United States alone is approximately 1 in 12,000 live births (3).

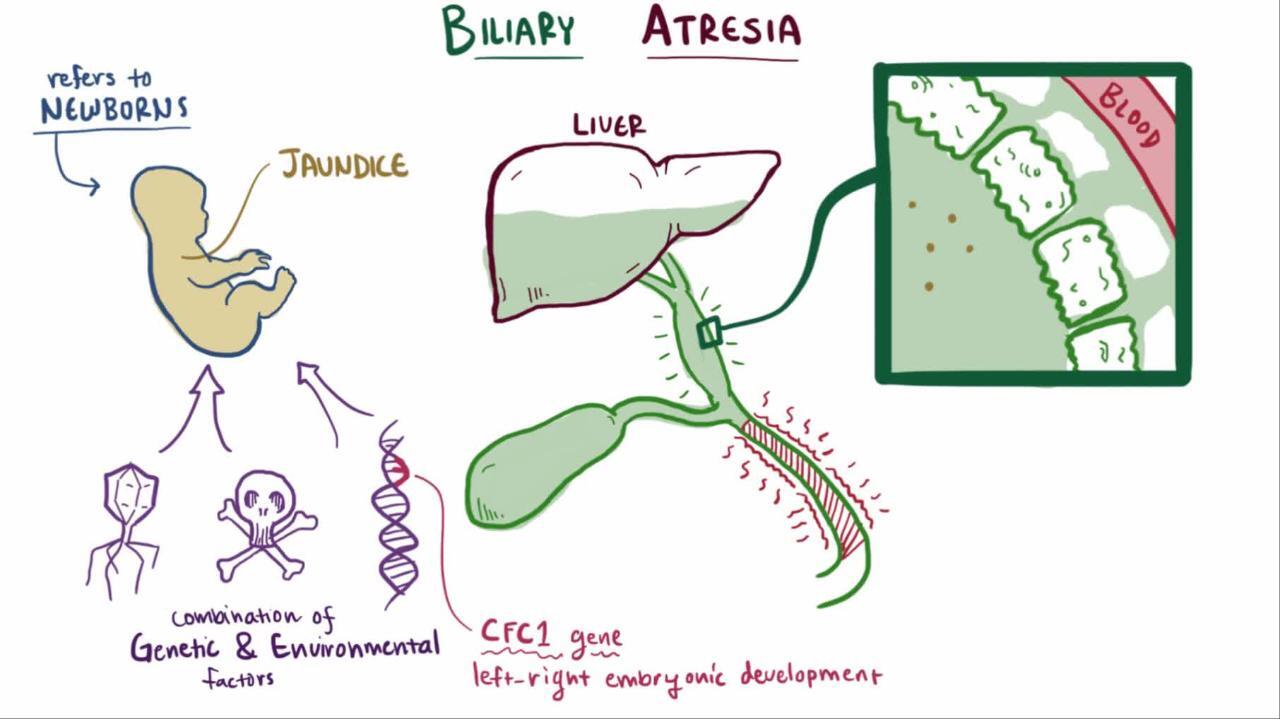

In most cases, biliary atresia presents several weeks to months after birth, probably after inflammation and scarring of the extrahepatic (and sometimes intrahepatic) bile ducts (4). It is rarely present in preterm infants or in neonates at birth (or is unrecognized in neonates).

The cause of the inflammatory response is unknown. Several infectious organisms have been implicated, including cytomegalovirus, Ebstein-Barr virus, reovirus, and rotavirus, but no definitive association has been noted (5). In addition, there may be a genetic component and multiple implicated genes (ADD3, EFEMP1 , AFAP1, TUSC3, MAN1A2, ARF6, CRIPTO, NODAL, LEFTY, GPC) (2).

Biliary atresia can lead to cirrhosis, with progressive, irreversible scarring of the liver. The differential diagnosis includes many other etiologies, but early diagnosis of biliary atresia is crucial because portojejunostomy (Kasai procedure) before 45 to 60 days of life gives the infant the best chance of survival with the native liver (6). Cirrhosis can develop by 2 months of age and progresses if the defect is not treated.

Many infants with biliary atresia have other congenital disorders, including polysplenia/asplenia (biliary atresia splenic malformation [BASM] syndrome) in 50%, congenital heart disease in approximately 15%, intestinal atresia in up to 5%, situs inversus, and renal anomalies (2).

General references

1. Harpavat S, Garcia-Prats JA, Anaya C, et al. Diagnostic yield of newborn screening for biliary atresia using direct or conjugated bilirubin measurements. JAMA. 2020;323(12):1141–1150. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.0837

2. Tam PKH, Wells RG, Tang CSM, et al. Biliary atresia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024;10(1):47. Published 2024 Jul 11. doi:10.1038/s41572-024-00533-x

3. Fawaz R, Baumann U, Ekong U, et al. Guideline for the Evaluation of Cholestatic Jaundice in Infants: Joint Recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;64(1):154-168. doi:10.1097/MPG.0000000000001334

4. Lendahl U, Lui VCH, Chung PHY. Biliary Atresia - emerging diagnostic and therapy opportunities. EBioMedicine. 2021;74:103689. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103689

5. Miller PN, Baskaran S, Nijagal A. Immunology of Biliary Atresia. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2024;33(6):151474. doi:10.1016/j.sempedsurg.2025.151474

6. Robie DK, Overfelt SR, Xie L. Differentiating biliary atresia from other causes of cholestatic jaundice. Am Surg. 2014;80(9):827-831.

Symptoms and Signs of Biliary Atresia

Infants with biliary atresia have jaundice and often have dark urine (containing conjugated bilirubin), acholic stools, and hepatosplenomegaly. The presence of cholestatic jaundice at 2 weeks of age in an otherwise healthy infant warrants investigation to determine the underlying cause.

By 2 to 3 months of age, infants may have poor growth with undernutrition, pruritus, irritability, and splenomegaly.

Untreated, hepatic fibrosis progresses to cirrhosis resulting in portal hypertension, abdominal distention resulting from ascites, dilated abdominal veins, and upper gastrointestinal bleeding resulting from esophageal varices.

Diagnosis of Biliary Atresia

Total and direct bilirubin

Liver tests

Serum alpha-1 antitrypsin levels (to rule out alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency)

Sweat chloride test (to rule out cystic fibrosis)

Abdominal ultrasound

Hepatobiliary scan

Usually, liver biopsy and intraoperative cholangiography

Biliary atresia is identified by an elevation in both total and direct bilirubin. The serum alpha-1 antitrypsin levels should be determined because alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is another relatively common cause of cholestasis. Tests that are needed to evaluate the liver include albumin, liver enzymes, prothrombin time/partial thromboplastin time (PT/PTT), and ammonia level. Matrix metalloproteinase-7 is also highly sensitive (94%) for biliary atresia (is another relatively common cause of cholestasis. Tests that are needed to evaluate the liver include albumin, liver enzymes, prothrombin time/partial thromboplastin time (PT/PTT), and ammonia level. Matrix metalloproteinase-7 is also highly sensitive (94%) for biliary atresia (1).

The sweat chloride concentration should also be determined to rule out cystic fibrosis (2). Frequently, additional testing is needed to evaluate for other metabolic, infectious, genetic, and endocrine causes of neonatal cholestasis (3). Elevated serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels, and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) support the diagnosis of biliary atresia but do not rule out other forms of cholestasis.

Abdominal ultrasound is noninvasive and can assess liver size and certain abnormalities of the gallbladder and common bile duct. Infants with biliary atresia often have a small contracted gallbladder or one that cannot be seen. However, these findings are nonspecific.

A hepatobiliary scan using hydroxy iminodiacetic acid (HIDA scan) should also be performed; excretion of contrast into the intestine rules out biliary atresia, but lack of excretion is not diagnostic of biliary atresia because severe neonatal hepatitis and other causes of cholestasis may also cause little or no excretion.

A definitive diagnosis of biliary atresia is made with a liver biopsy and intraoperative cholangiography (4). Sometimes, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) can be performed to aid in the diagnosis. The classic histologic findings are enlarged portal tracks with fibrosis and bile duct proliferation. Bile plugs may also be noted in the bile ducts. Intraoperative cholangiography reveals the lack of a patent extrahepatic bile duct.

The differential diagnosis includes other causes of neonatal cholestatic jaundice, including Alagille syndrome, alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, cystic fibrosis, metabolic disorders (eg, galactosemia, tyrosinemia, congenital infections, and neonatal hepatitis (4).

Diagnosis references

1. Pandurangi S, Mourya R, Nalluri S, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of serum matrix metalloproteinase-7 as a biomarker of biliary atresia in a large North American cohort. Hepatology. 2024;80(1):152-162. doi:10.1097/HEP.0000000000000827

2. Kobelska-Dubiel N, Klincewicz B, Cichy W. Liver disease in cystic fibrosis. Prz Gastroenterol. 2014;9(3):136-141. doi:10.5114/pg.2014.43574

3. Heinz N, Vittorio J. Treatment of Cholestasis in Infants and Young Children. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2023;25(11):344-354. doi:10.1007/s11894-023-00891-8

4. Tam PKH, Wells RG, Tang CSM, et al. Biliary atresia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024;10(1):47. Published 2024 Jul 11. doi:10.1038/s41572-024-00533-x

Treatment of Biliary Atresia

Intraoperative cholangiogram

Portojejunostomy (Kasai procedure)

Frequently liver transplantation

Infants with presumed biliary atresia require surgical exploration with an intraoperative cholangiogram. If biliary atresia is confirmed, a portojejunostomy (Kasai procedure) should be performed as part of the same surgical procedure. Ideally, this procedure should be performed in the first month of life. Long-term prognosis is best if the procedure is done < 30 days after birth; if done ≥ 60 days after birth, the prognosis significantly worsens (1).

Postoperatively, many patients have significant chronic problems, including persistent cholestasis, recurrent ascending cholangitis, and growth and weight faltering (formerly known as failure to thrive). If cholestasis persists for ≥ 3 months postoperatively, referral to a transplant center should be considered (2). Prophylactic antibiotics (eg, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, neomycin) are frequently prescribed for a year postoperatively in an attempt to prevent ascending cholangitis. Medications that increase bile production (choleretic agents), such as ursodiol, are frequently used postoperatively. Nutritional therapy including supplemental fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) is very important to ensure adequate intake to support growth (). Prophylactic antibiotics (eg, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, neomycin) are frequently prescribed for a year postoperatively in an attempt to prevent ascending cholangitis. Medications that increase bile production (choleretic agents), such as ursodiol, are frequently used postoperatively. Nutritional therapy including supplemental fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) is very important to ensure adequate intake to support growth (3, 4).

Infants who cannot undergo portojejunostomy often require liver transplantation.

Treatment references

1. Hoshino E, Muto Y, Sakai K, Shimohata N, Urayama KY, Suzuki M. Age at surgery and native liver survival in biliary atresia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Pediatr. 2023;182(6):2693-2704. doi:10.1007/s00431-023-04925-1

2. Squires RH, Ng V, Romero R, et al. Evaluation of the pediatric patient for liver transplantation: 2014 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American Society of Transplantation and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. Hepatology. 2014;60(1):362-398. doi:10.1002/hep.27191

3. Mouzaki M, Bronsky J, Gupte G, et al. Nutrition support of children with chronic liver diseases: A joint position paper of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2019;69(4):498–511. doi:10.1097/MPG.0000000000002443

4. Heinz N, Vittorio J. Treatment of Cholestasis in Infants and Young Children. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2023;25(11):344-354. doi:10.1007/s11894-023-00891-8

Prognosis for Biliary Atresia

Biliary atresia is progressive and, if untreated, results in cirrhosis with portal hypertension by several months of age, then liver failure and death by 1 year of age.

Portojejunostomy is ineffective in some infants and only palliative in most infants. After portojejunostomy, 30% of patients require a liver transplantation at a median age of 6 years, whereas up to 80% require transplantation by age 20 (1, 2). Long-term survival after liver transplantation (with or without prior portojejunostomy) is approximately 80% (3, 4).

Prognosis references

1. Squires RH, Ng V, Romero R, et al. Evaluation of the pediatric patient for liver transplantation: 2014 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American Society of Transplantation and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. Hepatology. 2014;60(1):362-398. doi:10.1002/hep.27191

2. Chung PHY, Chan EKW, Yeung F, et al. Life long follow up and management strategies of patients living with native livers after Kasai portoenterostomy. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):11207. Published 2021 May 27. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-90860-w

3. Lendahl U, Lui VCH, Chung PHY. Biliary Atresia - emerging diagnostic and therapy opportunities. EBioMedicine. 2021;74:103689. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103689

4. Sundaram SS, Mack CL, Feldman AG, et al. Biliary atresia: Indications and timing of liver transplantation and optimization of pretransplant care. Liver Transpl. 2017;23(1):96-109. doi:10.1002/lt.24640

Key Points

In most cases, biliary atresia presents several weeks after birth, probably after inflammation and scarring of the extrahepatic (and sometimes intrahepatic) bile ducts.

Infants have jaundice and often have dark urine (containing conjugated bilirubin), acholic stools, and hepatosplenomegaly.

By age 2 to 3 months, infants may have poor growth with malnutrition, pruritus, irritability, and splenomegaly.

Diagnose using blood test results, ultrasound, hepatobiliary scan, liver biopsy, and intraoperative cholangiography.

Treatment is with portojejunostomy (Kasai procedure) performed as early as possible, ideally before the age of 30 days; if done 60 days or more after birth, the rate of success of the procedure is markedly reduced.

Often, liver transplantation is subsequently required.

Drugs Mentioned In This Article