Topic Resources

(See also Overview of Congenital Gastrointestinal Anomalies.)

The incidence of biliary atresia in the United States is about 1/8,000 to 1/18,000 live births (1).

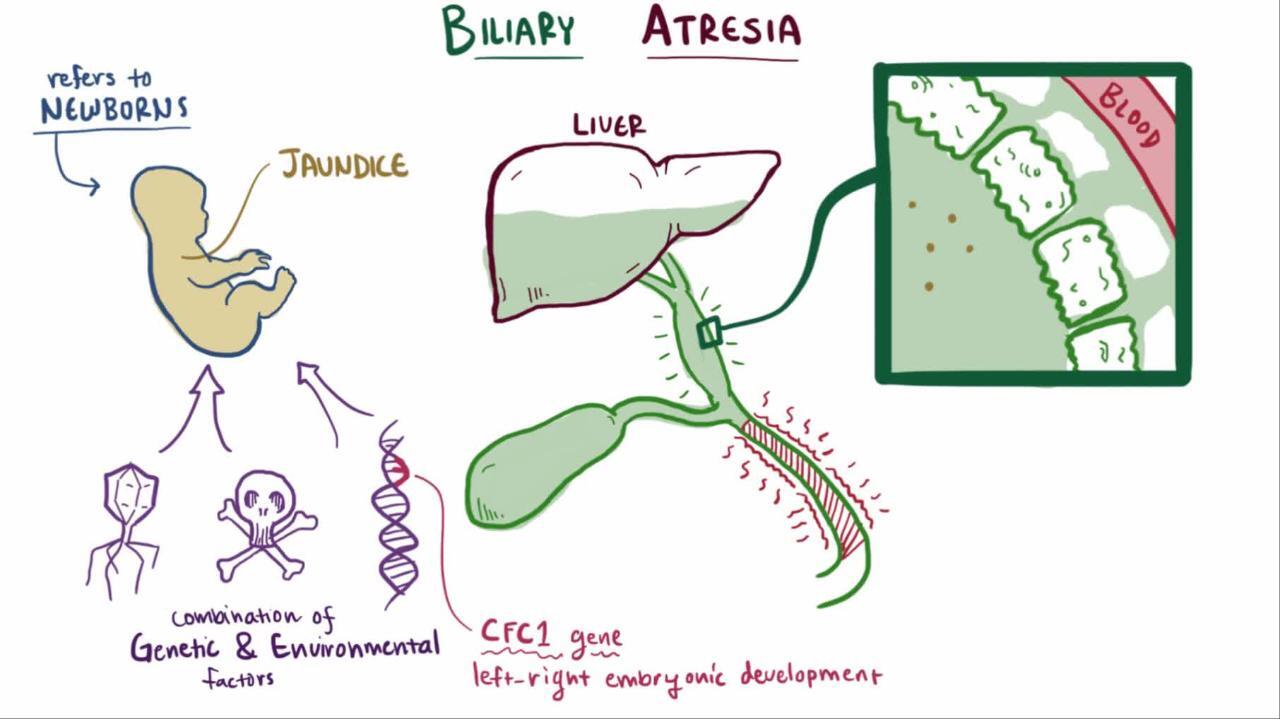

In most cases, biliary atresia manifests several weeks to months after birth, probably after inflammation and scarring of the extrahepatic (and sometimes intrahepatic) bile ducts (2). It is rarely present in premature infants or in neonates at birth (or is unrecognized in neonates). The cause of the inflammatory response is unknown. Several infectious organisms have been implicated, including reovirus type 3 and cytomegalovirus, but no definitive association has been noted. In addition, there may be a genetic component with defects in one of several genes (CFC1, FOXA2).

Biliary atresia can lead to cirrhosis, with progressive, irreversible scarring of the liver. Cirrhosis can develop by 2 months of age and progresses if the defect is not treated.

Approximately 15 to 25% of infants with biliary atresia have other congenital defects, including polysplenia/asplenia, intestinal atresia, situs inversus, and cardiac anomalies or renal anomalies.

General references

1. Harpavat S, Garcia-Prats JA, Anaya C, et al: Diagnostic yield of newborn screening for biliary atresia using direct or conjugated bilirubin measurements. JAMA 323(12):1141–1150, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.0837

2. Lendahl U, Lui VCH, Chung PHY: Biliary Atresia - emerging diagnostic and therapy opportunities. EBioMedicine 74:103689, 2021. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103689

Symptoms and Signs of Biliary Atresia

Infants with biliary atresia are jaundiced and often have dark urine (containing conjugated bilirubin), acholic stools, and hepatosplenomegaly. The presence of cholestatic jaundice at 2 weeks of age in an otherwise healthy infant warrants investigation to determine the underlying cause. The differential diagnosis includes many other etiologies, but early diagnosis of biliary atresia is crucial because portojejunostomy (Kasai procedure) before 45 to 60 days of life gives the infant the best chance for survival with the native liver (1).

By 2 to 3 months of age, infants may have poor growth with malnutrition, pruritus, irritability, and splenomegaly.

Untreated, hepatic fibrosis progresses to cirrhosis resulting in portal hypertension, abdominal distention resulting from ascites, dilated abdominal veins, and upper gastrointestinal bleeding resulting from esophageal varices.

Symptoms and signs reference

1. Robie DK, Overfelt SR, Xie L: Differentiating biliary atresia from other causes of cholestatic jaundice. Am Surg 80(9):827-831, 2014. PMID: 25197861

Diagnosis of Biliary Atresia

Total and direct bilirubin

Liver function tests

Serum alpha-1 antitrypsin levels (to rule out alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency)

Sweat chloride test (to rule out cystic fibrosis)

Abdominal ultrasonography

Hepatobiliary scan

Usually, liver biopsy and intraoperative cholangiography

Biliary atresia is identified by an elevation in both total and direct bilirubin. The serum alpha-1 antitrypsin levels should be determined because alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is another relatively common cause of cholestasis. Tests that are needed to evaluate the liver include albumin, liver enzymes, prothrombin time/partial thromboplastin time (PT/PTT), and ammonia level. is another relatively common cause of cholestasis. Tests that are needed to evaluate the liver include albumin, liver enzymes, prothrombin time/partial thromboplastin time (PT/PTT), and ammonia level.

The sweat chloride concentration should also be determined to rule out cystic fibrosis (1). Frequently, additional testing is needed to evaluate for other metabolic, infectious, genetic, and endocrine causes of neonatal cholestasis. Elevated serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels, and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) support the diagnosis of biliary atresia but do not rule out other forms of cholestasis.

Abdominal ultrasonography is noninvasive and can assess liver size and certain abnormalities of the gallbladder and common bile duct. Infants with biliary atresia often have a small contracted gallbladder or one that cannot be seen. However, these findings are nonspecific. A hepatobiliary scan using hydroxy iminodiacetic acid (HIDA scan) should also be done; excretion of contrast into the intestine rules out biliary atresia, but lack of excretion is not diagnostic of biliary atresia, because severe neonatal hepatitis and other causes of cholestasis may also cause little or no excretion.

A definitive diagnosis of biliary atresia is made with a liver biopsy and intraoperative cholangiography. Sometimes, ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography) can be done to aid in the diagnosis. The classic histologic findings are enlarged portal tracks with fibrosis and bile duct proliferation. Bile plugs may also be noted in the bile ducts. Intraoperative cholangiography reveals the lack of a patent extrahepatic bile duct.

Diagnosis reference

1. Kobelska-Dubiel N, Klincewicz B, Cichy W: Liver disease in cystic fibrosis. Prz Gastroenterol 9(3):136-141, 2014. doi:10.5114/pg.2014.43574

Treatment of Biliary Atresia

Intraoperative cholangiogram

Portojejunostomy (Kasai procedure)

Frequently liver transplantation

Infants with presumed biliary atresia require surgical exploration with an intraoperative cholangiogram. If biliary atresia is confirmed, a portojejunostomy (Kasai procedure) should be done as part of the same surgical procedure. Ideally, this procedure should be done in the first month of life. If done 60 days or more after birth, the prognosis significantly worsens.

Postoperatively, many patients have significant chronic problems, including persistent cholestasis, recurrent ascending cholangitis, and failure to thrive. If cholestasis persists for ≥ 3 months postoperatively, referral to a transplant center should be considered. Prophylactic antibiotics (eg, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or neomycin) are frequently prescribed for a year postoperatively in an attempt to prevent ascending cholangitis. Medications that increase bile production (choleretic agents), such as ursodiol, are frequently used postoperatively. Nutritional therapy including supplemental fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) is very important to ensure adequate intake to support growth (Postoperatively, many patients have significant chronic problems, including persistent cholestasis, recurrent ascending cholangitis, and failure to thrive. If cholestasis persists for ≥ 3 months postoperatively, referral to a transplant center should be considered. Prophylactic antibiotics (eg, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or neomycin) are frequently prescribed for a year postoperatively in an attempt to prevent ascending cholangitis. Medications that increase bile production (choleretic agents), such as ursodiol, are frequently used postoperatively. Nutritional therapy including supplemental fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) is very important to ensure adequate intake to support growth (1). Even with optimal therapy, approximately 50% of infants will develop cirrhosis and require liver transplantation.

Frequently, infants who cannot undergo portojejunostomy require liver transplantation by 1 year of age.

Treatment reference

1. Mouzaki M, Bronsky J, Gupte G, et al: Nutrition support of children with chronic liver diseases: A joint position paper of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 69(4):498–511, 2019. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002443

Prognosis for Biliary Atresia

Biliary atresia is progressive and, if untreated, results in cirrhosis with portal hypertension by several months of age, then liver failure and death by 1 year of age. Portojejunostomy is ineffective in some infants and only palliative in most infants. Long-term survival after liver transplantation (with or without prior portojejunostomy) is approximately 80% (1, 2).

Prognosis references

1. Lendahl U, Lui VCH, Chung PHY: Biliary Atresia - emerging diagnostic and therapy opportunities. EBioMedicine 74:103689, 2021. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103689

2. Sundaram SS, Mack CL, Feldman AG, et al: Biliary atresia: Indications and timing of liver transplantation and optimization of pretransplant care. Liver Transpl 23(1):96-109, 2017. doi:10.1002/lt.24640

Key Points

In most cases, biliary atresia manifests several weeks after birth, probably after inflammation and scarring of the extrahepatic (and sometimes intrahepatic) bile ducts.

Infants are jaundiced and often have dark urine (containing conjugated bilirubin), acholic stools, and hepatosplenomegaly.

By age 2 to 3 months, infants may have poor growth with malnutrition, pruritus, irritability, and splenomegaly.

Diagnose using blood test results, ultrasonography, hepatobiliary scan, liver biopsy, and intraoperative cholangiography.

Treatment is with portojejunostomy (Kasai procedure) done as early as possible, ideally before the age of 30 days; if done 60 days or more after birth, the rate of success of the procedure is markedly reduced.

Often, liver transplantation is subsequently required.