- Emergency Treatment of Arrhythmias

- Atrial Fibrillation

- Atrial Fibrillation and Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome (WPW Syndrome)

- Atrial Flutter

- Atrioventricular Block

- Bundle Branch Block and Fascicular Block

- Ectopic Supraventricular Arrhythmias

- Reentrant (Paroxysmal) Supraventricular Tachycardias (PSVT)

- Sick Sinus Syndrome

- Syndrome of Inappropriate Sinus Tachycardia

- Torsades de Pointes Ventricular Tachycardia

- Ventricular Fibrillation (VF)

- Ventricular Premature Beats (VPB)

- Ventricular Tachycardia (VT)

- Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome (WPW Syndrome)

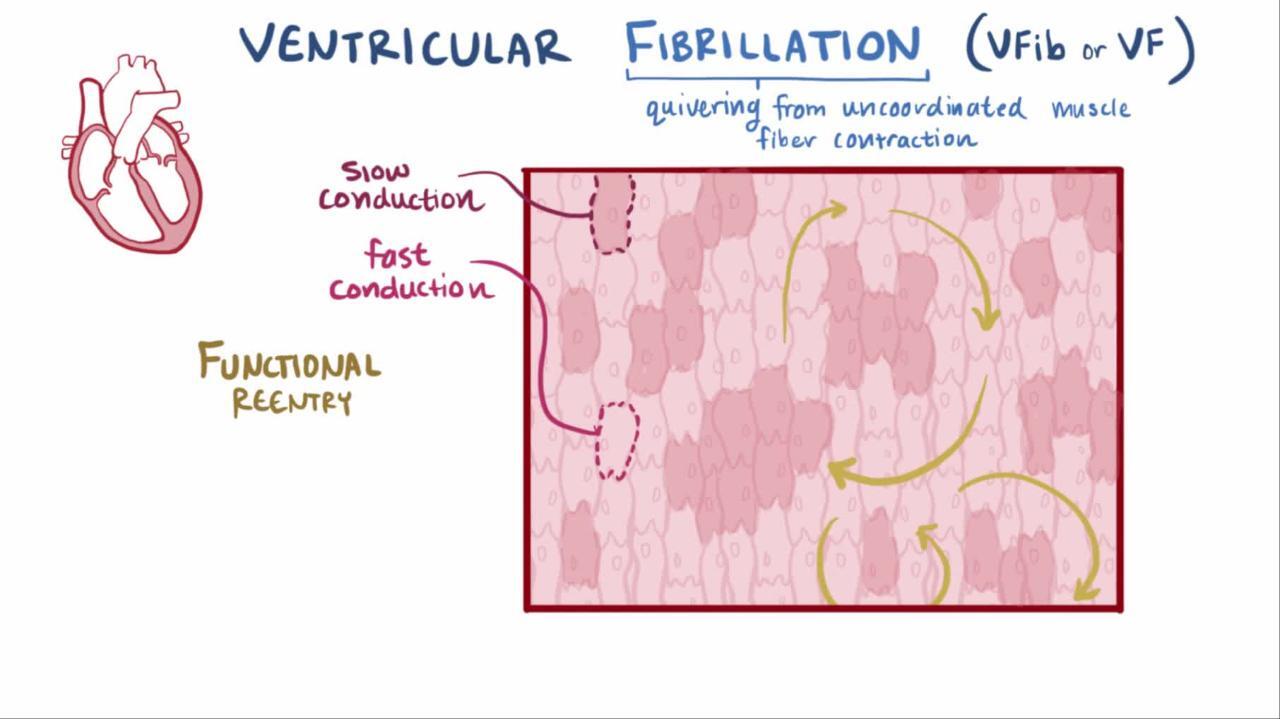

Ventricular fibrillation causes uncoordinated quivering of the ventricle with no useful contractions. It causes immediate syncope and death within minutes. Treatment is with cardiopulmonary resuscitation, including immediate defibrillation.

(See also Overview of Arrhythmias.)

Ventricular fibrillation (VF) is due to multiple wavelet reentrant electrical activity and is manifested on electrocardiogram (ECG) by ultrarapid baseline undulations that are irregular in timing and morphology.

Although early reports noted that VF was the presenting rhythm for about 75% of patients in cardiac arrest (1), the proportion of cardiac arrests due to VF has been decreasing. More recently, VF has been reported to be the presenting rhythm in about 40% of cardiac arrests (2). Nevertheless, because VF leads to asystole with time, this proportion is an underestimate. Accordingly, VF is still the terminal event in many disorders. Overall, most patients with VF have an underlying heart disorder (typically ischemic cardiomyopathy, but also hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or dilated cardiomyopathy, or other arrhythmogenic cardiovascular disorders). Patients in whom no underlying disorder is detected are considered to have idiopathic VF. Risk of VF in any disorder is increased by electrolyte abnormalities, acidosis, hypoxemia, or ischemia.

Ventricular fibrillation is much less common among infants and children, in whom asystole is the more common presentation of cardiac arrest.

© Springer Science+Business Media

Image courtesy of L. Brent Mitchell, MD.

Idiopathic ventricular fibrillation

Patients who have been resuscitated from VF cardiac arrest are evaluated for cardiac disease, particularly coronary artery disease, cardiomyopathies, and channelopathies (3). If comprehensive electrocardiographic, imaging, and provocative testing do not identify any such causative disorder, the patient is considered to have idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. It is thought that some of these patients likely have an unrecognized or unknown genetic disorder. Because of the possibility that the disorder is familial, it is recommended that family members undergo close surveillance for possible cardiac events (eg, syncope, palpitations) and, should any occur, undergo testing, including ECG, exercise stress testing, and echocardiography. Genetic testing of survivors and cascade genetic testing of family members is done in selected patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy or a suspected channelopathy (3) (see also Arrhythmogenic Cardiac Disorders). Treatment is an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (3).

General references

1. Weaver WD, Cobb LA, Hallstrom AP, et al: Considerations for improving survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Ann Emerg Med 15:1181–1186, 1986. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(86)80862-9

2. Cobb LA, Fahrenbruch CE, Olsufka M, et al: Changing incidence of out-of-hospital ventricular fibrillation, 1980-2000. JAMA 288(23):3008–3013, 2002. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.23.3008

3. Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, et al: 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 72:e91–e220, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.054

Treatment of Ventricular Fibrillation

Defibrillation

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

Treatment of ventricular fibrillation is with cardiopulmonary resuscitation, including defibrillation, beginning with biphasic 120 to 200 joules (or monophasic 360 joules). The success rate for immediate defibrillation (within seconds as can be achieved by an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator) is about 99% provided that overwhelming pump failure does not preexist. Thereafter, the first shock defibrillation success rate decreases by about 10% per minute (1).

Patients who have VF without a reversible or transient cause are at high risk of future VF events and of sudden death. Most of these patients require an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; many require concomitant antiarrhythmic medications to reduce the frequency of subsequent episodes of ventricular tachycardia and VF (2).

Treatment references

1. van Alem AP, Chapman FW, Lank P, et al: A prospective, randomised and blinded comparison of first shock success of monophasic and biphasic waveforms in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 58(1):17–24, 2023. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(03)00106-0

2. Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, et al: 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 72:e91–e220, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.054