Restrictive cardiomyopathy includes a group of heart disorders in which the walls of the ventricles (the 2 lower chambers of the heart) become stiff, but not necessarily thickened, and resist normal filling with blood between heartbeats.

Topic Resources

Restrictive cardiomyopathy may occur when heart muscle is gradually infiltrated or replaced by scar tissue or when abnormal substances accumulate in the heart muscle.

Shortness of breath, fluid accumulation in the tissues, abnormal heart rhythms, and awareness of heartbeats (palpitations) are common symptoms.

The diagnosis is based on results of a physical examination, electrocardiography (ECG), echocardiography, radionuclide imaging, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), cardiac biopsy, and cardiac catheterization.

Treatment is not often helpful, although sometimes doctors are able to treat the cause.

Cardiomyopathy refers to progressive impairment of the structure and function of the muscular walls of the heart chambers. There are three main types of cardiomyopathy. In addition to restrictive cardiomyopathy, there are dilated cardiomyopathy and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (see also Overview of Cardiomyopathy).

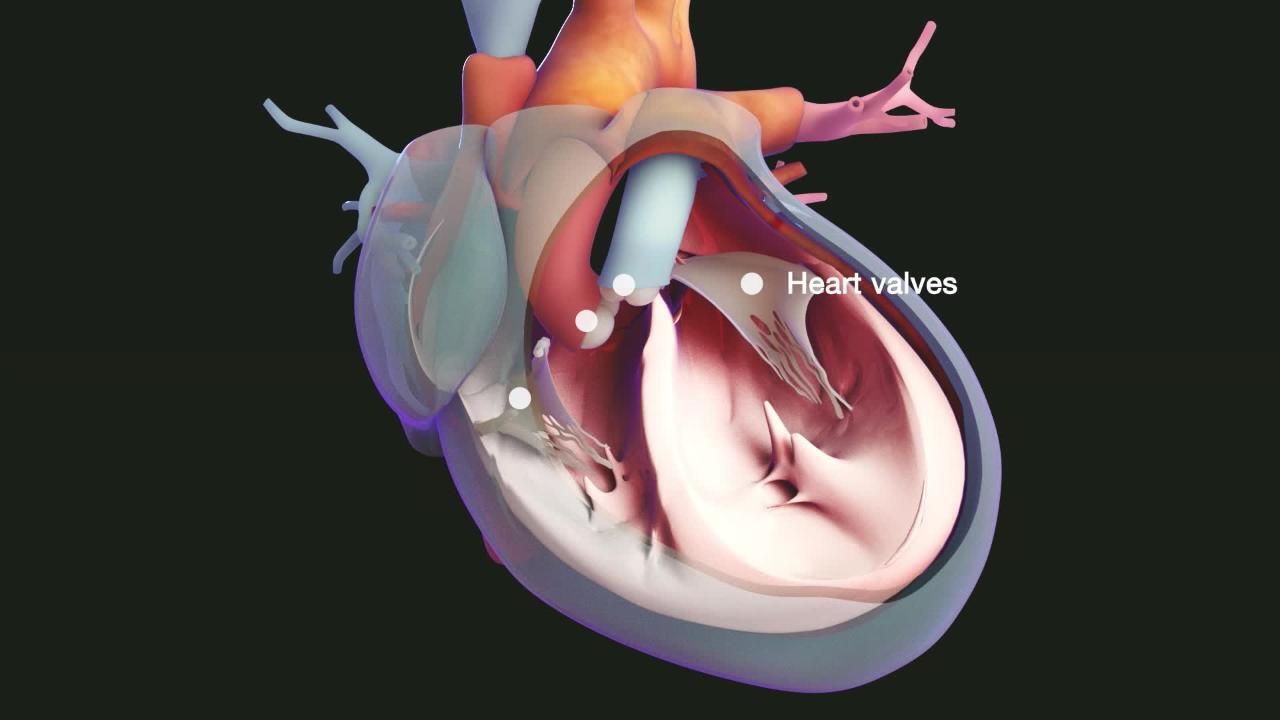

The term cardiomyopathy is used only when a disorder directly affects the heart muscle. Other heart disorders such as coronary artery disease and heart valve disorders, also can eventually cause the ventricles to enlarge and heart failure.

Restrictive cardiomyopathy is the least common form of cardiomyopathy and shares many features with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Its cause is usually unknown.

There are 2 basic types of restrictive cardiomyopathy:

The heart muscle is gradually replaced by scar tissue.

Abnormal substances accumulate in the heart muscle.

A congenital form of restrictive cardiomyopathy occurs in infants and children who have endocardial fibroelastosis. In this rare disorder, a thickened layer of fibrous tissue lines the left ventricle. Endomyocardial fibrosis commonly occurs in tropical regions and affects both the left and right ventricles.

Scarring

Scarring of heart muscle may occur for unknown reasons. It can also result from injury due to accumulation of abnormal substances in the body or treatments, such as radiation therapy that may be given for treatment of a chest tumor or certain drugs used to treat certain disorders.

Accumulation of abnormal substances

Various substances may accumulate in the heart as a result of various disorders. The accumulated substances interfere with the heart muscle's ability to contract and relax.

For example, in people who have iron overload (hemochromatosis), the body contains too much iron, so iron may accumulate in the heart muscle.

In hypereosinophilic syndrome, eosinophils (a type of white blood cell) may accumulate in the heart muscle. Hypereosinophilic syndrome most often occurs in tropical regions.

In amyloidosis, amyloid (an unusual protein not normally present in the body) may accumulate in heart muscle and other tissues. Amyloidosis is more common among older adults and can sometimes be hereditary.

Other examples are tumors and granuloma tissue (abnormal collections of certain white blood cells that form in response to chronic inflammation), which, for example, develops in people who have sarcoidosis.

Symptoms of Restrictive Cardiomyopathy

Restrictive cardiomyopathy causes heart failure with shortness of breath during exertion and when lying flat, and fluid accumulation and swelling in tissues (edema).

Chest pain and fainting (syncope) are less likely than in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, but abnormal heart rhythms (arrhythmias) are common. Fatigue may also occur.

Usually, symptoms do not occur during rest, because in restrictive cardiomyopathy, the heart can supply the body with enough blood and oxygen during rest, even though the stiff heart resists filling with blood. Symptoms occur during exercise, when the stiff heart cannot pump enough blood to meet the body’s increased need for blood and oxygen.

Diagnosis of Restrictive Cardiomyopathy

Echocardiography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the heart

Sometimes, cardiac catheterization and biopsy of the heart

Restrictive cardiomyopathy is one of the possible causes investigated when a person has heart failure.

The diagnosis is based largely on the combined results of a physical examination, electrocardiography (ECG), chest x-ray, and echocardiography. ECG can typically detect abnormalities in the heart’s electrical activity, but these abnormalities are not specific enough for a diagnosis.

Echocardiography shows that the atria (the upper chambers if the heart) are enlarged and that the heart is functioning normally only when the heart contracts (during systole). MRI can detect abnormal texture in heart muscle due to accumulation of or infiltration with abnormal substances, such as iron and amyloid. Sometimes, other imaging techniques such as radionuclide imaging of the heart are helpful.

Doctors sometimes do cardiac catheterization in people with severe symptoms, such as chest pain, difficulty breathing, or fainting. Cardiac catheterization is an invasive procedure in which a catheter is threaded from a blood vessel in the arm, neck, or leg into the heart. The procedure is used to measure pressures in the heart chambers and to remove a sample of heart muscle for examination under a microscope (biopsy), which may enable doctors to identify an infiltrating substance.

Sometimes, other specialized tests may be needed to determine the disorder causing the cardiomyopathy.

More than half the time, no specific cause for restrictive cardiomyopathy is found (idiopathic restrictive cardiomyopathy).

Treatment of Restrictive Cardiomyopathy

Treatment of the disorder causing restrictive cardiomyopathy

Sometimes, the disorder causing restrictive cardiomyopathy can be treated to prevent heart damage from worsening or even to partially reverse it. For example, removing blood at regular intervals reduces the amount of stored iron in people with iron overload. People who have sarcoidosis may take corticosteroids, which cause the granuloma tissue to disappear. Corticosteroids may also be helpful in eosinophilic infiltrative disorders. Medications used to decrease or control the symptoms of some types of amyloidosis may be helpful. However, many cases of restrictive cardiomyopathy have no specific treatment.

Survival varies depending on the cause. But prognosis is typically poor because the diagnosis is often made very late.

For most people, treatment is not very helpful. For example, diuretics, which are usually taken to treat heart failure, may help people who have troublesome leg swelling or shortness of breath. However, these medications also reduce the amount of blood entering the heart, which can worsen restrictive cardiomyopathy instead of improving it.

Medications commonly used in heart failure to reduce the heart’s workload, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, are usually not helpful because they reduce blood pressure too much. As a result, not enough blood reaches the rest of the body.

Similarly, digoxin is usually not helpful and is sometimes harmful in people with amyloidosis. Beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers are poorly tolerated in people with restrictive cardiomyopathy and have not been shown to improve survival. Similarly, digoxin is usually not helpful and is sometimes harmful in people with amyloidosis. Beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers are poorly tolerated in people with restrictive cardiomyopathy and have not been shown to improve survival.

Antiarrhythmics may be given to prevent or reduce symptoms in people with fast or irregular heart rhythms.

More Information

The following English-language resource may be useful. Please note that THE MANUAL is not responsible for the content of this resource.

American Heart Association: Restrictive cardiomyopathy: Provides comprehensive information on symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of restrictive cardiomyopathy