- Overview of Shoulder Dislocation Reduction Techniques

- How To Reduce Anterior Shoulder Dislocations Using the Davos Technique

- How To Reduce Anterior Shoulder Dislocations Using External Rotation (Hennepin Technique)

- How To Reduce Anterior Shoulder Dislocations Using the FARES Method

- How To Reduce Anterior Shoulder Dislocations Using Scapular Manipulation

- How To Reduce Anterior Shoulder Dislocations Using the Stimson Technique

- How To Reduce Anterior Shoulder Dislocations Using Traction-Countertraction

- How To Reduce Posterior Shoulder Dislocations

- How To Reduce a Posterior Elbow Dislocation

- How To Reduce a Radial Head Subluxation (Nursemaid Elbow)

- How To Reduce a Posterior Hip Dislocation

- How To Reduce a Lateral Patellar Dislocation

- How To Reduce an Ankle Dislocation

Traction-countertraction is often used to reduce anterior shoulder dislocations. The most commonly used traction-countertraction method requires one or more assistants, physical force, and occasionally, endurance. Procedural sedation and analgesia (PSA) usually is needed.

Traction-countertraction is no longer a first-line method for reduction but is still somewhat popular, owing mainly to its high success rate, safety, operator comfort, and mostly, tradition. It remains a reliable alternative technique.

(See also Overview of Shoulder Dislocation Reduction Techniques, Overview of Dislocations, and Shoulder Dislocations.)

Indications for Traction-Countertraction

Anterior dislocation of the shoulder

Reduction should be attempted soon (eg, within 30 minutes) after the diagnosis is made.

Reduction should be attempted immediately if an associated neurovascular deficit or skin tenting (due to a displaced bone fracture, or, less commonly, a fracture-dislocation, with potential for skin penetration or breakdown) is present. If a neurovascular deficit is suspected, a less forceful method is preferred. If an orthopedic surgeon is unavailable, closed reduction can be attempted, ideally using minimal force; if reduction is unsuccessful, it may need to be done in the operating room under general anesthesia.

Open dislocations require surgery, but closed reduction techniques and immobilization should be done as interim treatment if the orthopedic surgeon is unavailable and a neurovascular deficit is present.

Contraindications to Traction-Countertraction

Contraindications to simple closed reduction:

Greater tuberosity fracture with > 1 cm displacement

Significant Hill-Sachs deformity (≥ 20% humeral head deformity due to impaction against glenoid rim)

Surgical neck fracture (below the greater and lesser tuberosities)

Bankart fracture (anteroinferior glenoid rim) involving a bone fragment of over 20% and with glenohumeral instability

Proximal humeral fracture of 2 or more parts

These significant associated fractures require orthopedic evaluation and management, because of the risk of the procedure itself increasing displacement and injury severity.

Other reasons to consult with an orthopedic surgeon prior to reduction include

The joint is exposed (ie, an open dislocation)

The patient is a child, in whom a physeal (growth plate) fracture is often present; however, if a neurovascular deficit is present, reduction should be done immediately if the orthopedic surgeon is unavailable.

The dislocation is older than 7 to 10 days, due to an increased risk of damaging the axillary artery during the reduction, especially in older patients

Complications for Traction-Countertraction

Increased displacement of associated fractures

Axillary nerve injury, not common, caused by the traction placed on the arm during the reduction

Equipment for Traction-Countertraction

Intra-articular anesthetic (eg, 20 mL of 1% lidocaine, 20-mL syringe, 2-inch 20-gauge needle), antiseptic solution (eg, chlorhexidine, povidone iodine), gauze padsIntra-articular anesthetic (eg, 20 mL of 1% lidocaine, 20-mL syringe, 2-inch 20-gauge needle), antiseptic solution (eg, chlorhexidine, povidone iodine), gauze pads

Materials and personnel required for procedural sedation and analgesia

3 bed sheets

Shoulder immobilizer or sling and swathe

One or two assistants are needed for the traction-countertraction procedure.

Additional Considerations for Traction-Countertraction

Reduction attempts are more likely to succeed if patients are calm and can relax their muscles. Analgesia and sedation help patients relax, as may external distractions such as pleasant conversation.

Procedural sedation and analgesia (PSA) is often needed if substantial pain, anxiety, and muscle spasms impede the procedure.

Regional anesthesia can be used (eg, ultrasound-guided interscalene nerve block) but has the disadvantage of limiting post-reduction neurologic examination.

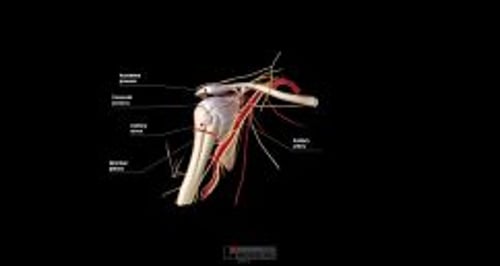

Relevant Anatomy for Traction-Countertraction

In most anterior dislocations, the humeral head is trapped outside and against the anterior lip of the glenoid fossa. Reduction techniques must distract the humeral head away from the lip and then return the humeral head into the fossa.

Deficits of the axillary nerve are the most frequent nerve deficits with anterior shoulder dislocations. They often resolve within several months, sometimes soon after the shoulder reduction.

Axillary artery injury is rare with anterior shoulder dislocations and suggests possible concurrent brachial plexus injury (because the brachial plexus surrounds the artery).

Positioning for Traction-Countertraction

Position the patient supine on the stretcher. Raise the stretcher to the level of your pelvis; lock the wheels of the stretcher.

Stand at the patient’s affected side at the level of the patient’s abdomen.

Have an assistant stand on the opposite side, somewhat cephalad to the patient’s shoulder level.

Step-by-Step Description of Traction-Countertraction

Neurovascular examination

Do a pre-procedure neurovascular examination of the affected arm, and repeat the examination after each reduction attempt. Generally, testing motor function is more reliable than testing sensation, partly because cutaneous nerve territories may overlap. Assess the following:

Distal pulses, capillary refill, cool extremity (axillary artery)

Light touch sensation of the lateral aspect of the upper arm (axillary nerve), thenar and hypothenar eminences (median and ulnar nerves), and dorsum of the 1st web space (radial nerve)

Shoulder abduction against resistance, while feeling the deltoid muscle for contraction (axillary nerve): However, if this test worsens the patient's pain, omit it until after the shoulder has been reduced.

Thumb-index finger apposition ("OK" gesture) and finger flexion against resistance (median nerve)

Finger abduction against resistance (ulnar nerve)

Wrist and finger extension against resistance (radial nerve)

Analgesia

Give analgesia. The best choice is usually intra-articular injection of local anesthetic. Procedural sedation and analgesia (PSA) is usually also needed. To give intra-articular analgesia:

The needle insertion site is about 2 cm inferior to the lateral edge of the acromion process (into the depression created by the absence of the humeral head).

Swab the area with antiseptic solution, and allow the antiseptic solution to dry for at least 1 minute.

Optional: Place a skin wheal of local anesthetic (≤ 1 mL) at the site.

Insert the intra-articular needle perpendicular to the skin, apply back pressure on the syringe plunger, and advance the needle medially and slightly inferiorly about 2 cm.

If any blood is aspirated from the joint, hold the needle hub motionless, switch to an empty syringe, aspirate all of the blood, and re-attach the anesthetic syringe.

Inject 10 to 20 mL of anesthetic solution (eg, 1% lidocaine).Inject 10 to 20 mL of anesthetic solution (eg, 1% lidocaine).

Wait for analgesia to occur (up to 15 to 20 minutes) before proceeding.

Give procedural sedation and analgesia.

Reduce the shoulder — Traction-countertraction

Wrap a sheet around the patient’s upper torso, passing the sheet under the axilla of the dislocated shoulder, and tie the ends of the sheet around the hips (not around the waist, which causes back strain) of the assistant standing at the opposite side of the stretcher.

Abduct the affected arm 45° and flex the elbow to 90°. Wrap a 2nd sheet around the flexed forearm proximally and then around your hips.

With your arms straight, hold the affected forearm with both hands, maintaining forearm flexion. Then, lean backward, which will apply traction to the patient’s arm. Simultaneously, have the assistant lean backward, creating the countertraction force to the axilla. The body weight of you and your assistant, rather than arm strength, provides the continuous force required for this technique.

If the sheet rides up on the patient’s forearm, correct for this situation by slightly increasing the forearm flexion.

The procedure may take many minutes to be successful. Use gentle, limited external rotation to facilitate reduction if necessary.

If there is muscle spasm or the patient resists the procedure, give more analgesic and/or sedative drugs.

If reduction does not occur, have a second assistant wrap a sheet around the affected humerus near the humeral head and apply a gentle lateral-cephalad force; this force leverages the distracted humeral head laterally towards the glenoid fossa.

Signs of a successful reduction may include a lengthening of the arm, a perceptible “clunk,” and brief deltoid fasciculation.

Aftercare for Traction-Countertraction

Successful reduction is preliminarily confirmed by restoration of a normal round shoulder contour, decreased pain, and by the patient's renewed ability to reach across the chest and place the palm of the hand upon the opposite shoulder.

Immobilize the shoulder with a sling and swathe or with a shoulder immobilizer.

Because the joint can spontaneously dislocate after successful reduction, do not delay immobilizing the joint.

Do a post-procedure neurovascular examination. A neurovascular deficit warrants immediate orthopedic evaluation.

Do post-procedure x-rays to confirm proper reduction and identify any coexisting fractures.

Arrange orthopedic follow-up.

Warnings and Common Errors for Traction-Countertraction

Apparent shoulder dislocation in a child is often a fracture involving the growth plate, which tends to fracture before the joint is disrupted.

Allow sufficient time for muscle spasm to resolve before proceeding through the procedure; too-rapid reduction is a common cause of failure with this technique.

Tips and Tricks for Traction-Countertraction

Wrapping the sheets around the operators’ hips (instead of the waist) prevents back strain. Tying the sheet using a proper square knot decreases the chance of the sheet untying during the procedure.

Adequate sedation and pain control are key.

Gentle external rotation is sometimes required to achieve the reduction.

In patients who return with increased pain within 48 hours after a reduction, hemarthrosis is likely (unless the shoulder has again dislocated). Aspirate the blood from the joint space (see How to Do Arthrocentesis of the Shoulder).