- Overview of Shoulder Dislocation Reduction Techniques

- How To Reduce Anterior Shoulder Dislocations Using the Davos Technique

- How To Reduce Anterior Shoulder Dislocations Using External Rotation (Hennepin Technique)

- How To Reduce Anterior Shoulder Dislocations Using the FARES Method

- How To Reduce Anterior Shoulder Dislocations Using Scapular Manipulation

- How To Reduce Anterior Shoulder Dislocations Using the Stimson Technique

- How To Reduce Anterior Shoulder Dislocations Using Traction-Countertraction

- How To Reduce Posterior Shoulder Dislocations

- How To Reduce a Posterior Elbow Dislocation

- How To Reduce a Radial Head Subluxation (Nursemaid Elbow)

- How To Reduce a Posterior Hip Dislocation

- How To Reduce a Lateral Patellar Dislocation

- How To Reduce an Ankle Dislocation

(See also Overview of Dislocations and Shoulder Dislocations.)

Among the techniques for reducing an anterior shoulder dislocation are

External rotation (eg, Hennepin technique) with abduction (eg, Milch technique) if needed

Reduction techniques for anterior dislocations generally use axial traction and/or external rotation. There is no single perfect or preferred technique. Most importantly, operators should be familiar with several techniques and use those appropriate to the patient's dislocation and clinical status (see Anterior Shoulder Dislocations: Treatment).

Some techniques have a high risk of injury and should not be performed. The original Hippocratic technique (operator's heel in the affected axilla to create countertraction) and the Kocher technique (which forcefully leverages the humerus) both have a high risk of injuries and complications and should not be performed (1).

Reduction attempts, particularly those performed without sedation, are more likely to succeed if the patient is relaxed and cooperating. Analgesia and sedation can help relieve muscle spasms, as can mental distractions such as conversation.

Patients should be offered analgesia as soon as practical. To decrease time to reduction and resultant pain relief, the patient may be offered one reduction attempt without analgesia with a gentle reduction method (eg, Davos, scapular manipulation, Hennepin, FARES). Intravenous analgesia and/or an intra-articular injection of anesthetic may be given early during the initial evaluation to allay pain during radiographs and other preprocedure preparations. Procedural sedation and analgesia (PSA) may be used for patients with anxiety and severe muscle spasms and for reduction methods requiring more force (eg, traction-countertraction and Stimson).

Reduction of a posterior dislocation or an inferior dislocation (luxatio erecta) usually involves a traction-countertraction technique. When possible, an orthopedic surgeon should be consulted prior to reducing these dislocations.

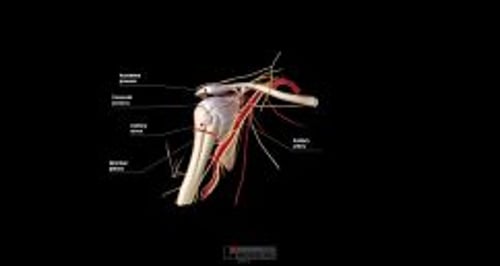

Neurovascular injury (eg, injury to the axillary nerve or artery) may result from the dislocation (most often with an anterior dislocation) or from the reduction procedure. Axillary nerve injury deficits usually resolve within a few months but prognosis depends on the mechanism and severity of nerve injury (2). Joints should be reduced as soon as possible because delays increase the risk of neurovascular complications. To avoid increasing muscle spasms, reductions should be performed gently and gradually, and reduction methods that use less force should be tried before those that use greater force. Choosing a gentle method is particularly important if a brachial plexus injury is suspected.

Neurovascular assessments are performed before the procedure and after each reduction attempt. The examination includes assessing distal pulses and digital capillary refill time (axillary artery), touch sensation of the lateral upper arm (axillary nerve), and function of the radial, median, and ulnar nerves (brachial plexus).

Consultation with an orthopedic surgeon should be obtained prior to reduction if the patient has a complicated shoulder injury, such as a:

Greater tuberosity fracture with > 1 cm displacement

Significant Hill-Sachs deformity (≥ 20% humeral head deformity due to impaction against glenoid rim)

Surgical neck fracture (below the greater and lesser tuberosities)

Bankart fracture (anteroinferior glenoid rim) involving a bone fragment of over 20% and with glenohumeral instability

Proximal humeral fracture of 2 or more parts

Other reasons to consult with an orthopedic surgeon prior to reduction include:

The joint is exposed (ie, an open fracture or dislocation where bone or fracture segments penetrate the skin)

The patient is a child, because a physeal (growth plate) fracture is often present

The dislocation is older than 7 to 10 days, due to an increased risk of damaging the axillary artery during the reduction, especially in older patients

Consultation with an orthopedic surgeon should be obtained after 2 or 3 failed attempts at closed reduction or after a successful reduction if:

A complicated shoulder injury is suspected (eg, dislocation plus fracture, axillary nerve injury, or rotator cuff tear)

The patient has a first-time dislocation

However, in all patients, if a neurovascular deficit is present, reduction must be performed immediately. If an orthopedic surgeon is unavailable, closed reduction can be attempted, ideally using minimal force; if reduction is unsuccessful, it may need to be performed in the operating room under general anesthesia.

Post-reduction radiographs should usually be performed to document a successful reduction and to check again for fractures. However, radiographs may not be necessary in patients with minimally traumatic recurrent anterior shoulder dislocations.

References

1. Dala-Ali B, Penna M, McConnell J, et al. Management of acute anterior shoulder dislocation. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(16):1209-1215. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2012-091300

2. Perlmutter GS, Apruzzese W. Axillary nerve injuries in contact sports: recommendations for treatment and rehabilitation. Sports Med. 1998;26(5):351-361. doi:10.2165/00007256-199826050-00005